The Sudbury & District Health Unit Alcohol Use and the Health of Our Community

Executive Summary

Preventing and reducing the harmful use of alcohol is a public health priority (WHO, 2014, p. 2). Alcohol use is causally linked to over 200 diseases and injuries (WHO, 1992). Globally, alcohol is estimated to cause 3.3 million deaths each year (WHO, 2015). It is linked to many different types of cancer, cardiovascular disease, gastro-intestinal disease, injury, and can impact sexual health, and pre- and post-natal health. Evidence has shown that as availability of alcohol increases, alcohol consumption and the harms associated with alcohol consumption also increases (Babor et al., 2010). In Canada, the impacts of alcohol use and misuse are costing the government through enforcement, healthcare, and lost productivity. In 2002, the indirect cost of alcohol was estimated at over $7 billion in Canada, and in Ontario, there was a deficit of over $456 million that was directly related to alcohol use (e.g., acute care, enforcement, and prevention) (Thomas, 2012). These findings support the need for the Sudbury & District Health Unit (SDHU) to work collectively with partners and external stakeholders to develop community-based strategies to address and reduce alcohol use and misuse and the harms associated with it, specifically within the SDHU service area. This report, Alcohol Use and the Health of Our Community, will inform these efforts and inform our community on emerging research on the health impacts of alcohol consumption and the trends on alcohol use behaviours in our community.

Under the Ontario Public Health Standards (OPHS) (Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, 2015), the SDHU is mandated to provide current and reliable data and evidence around the health effects of alcohol misuse and to inform the community of the significant social, economic, environmental, and health impacts of alcohol use and misuse in our community. This includes informing the community about Canada’s Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines (LRADG), which were developed to moderate alcohol consumption and reduce the harms associated with acute and chronic alcohol use.

Canada’s Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines:

Reduce your long-term health risks by drinking no more than:

- 10 drinks a week for women, with no more than 2 drinks a day most days

- 15 drinks a week for men, with no more than 3 drinks a day most days

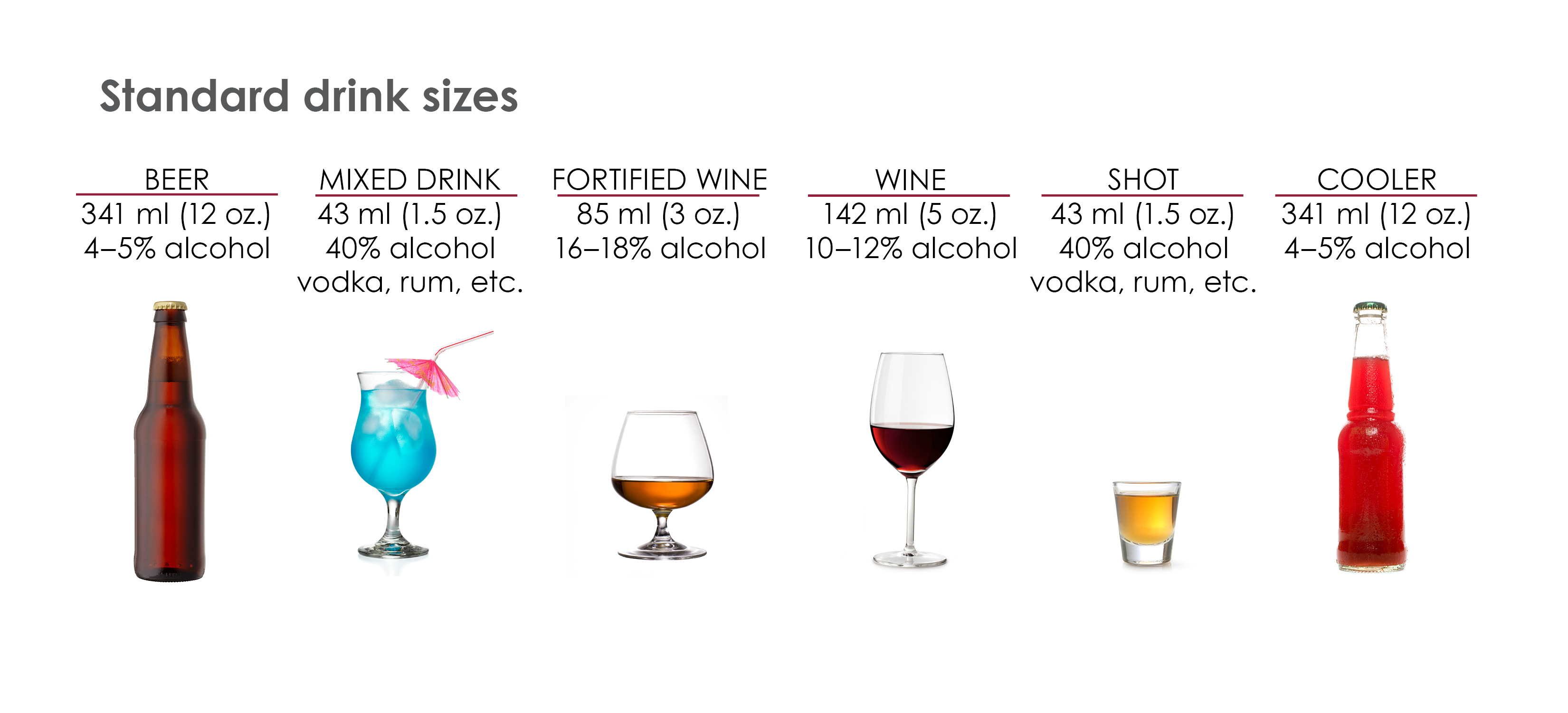

A standard service size

For these guidelines, a standard service size beverage is:

- 341 ml (12 oz) bottle of beer (4 to 5% alcohol)

- 341 ml (12 oz) cooler (4 to 5% alcohol)

- 43 ml (1.5 oz) mixed drink (40% alcohol)

- 43 ml (1.5 oz) shot (40% alcohol)

- 142 ml (5 oz) glass of wine (10 to 12% alcohol)

- 85 ml (3 oz) glass of fortified wine (16 to 18% alcohol)

Each standard serving sized alcoholic beverage noted above contains 13.4 grams of alcohol.

The following are key data from the report:

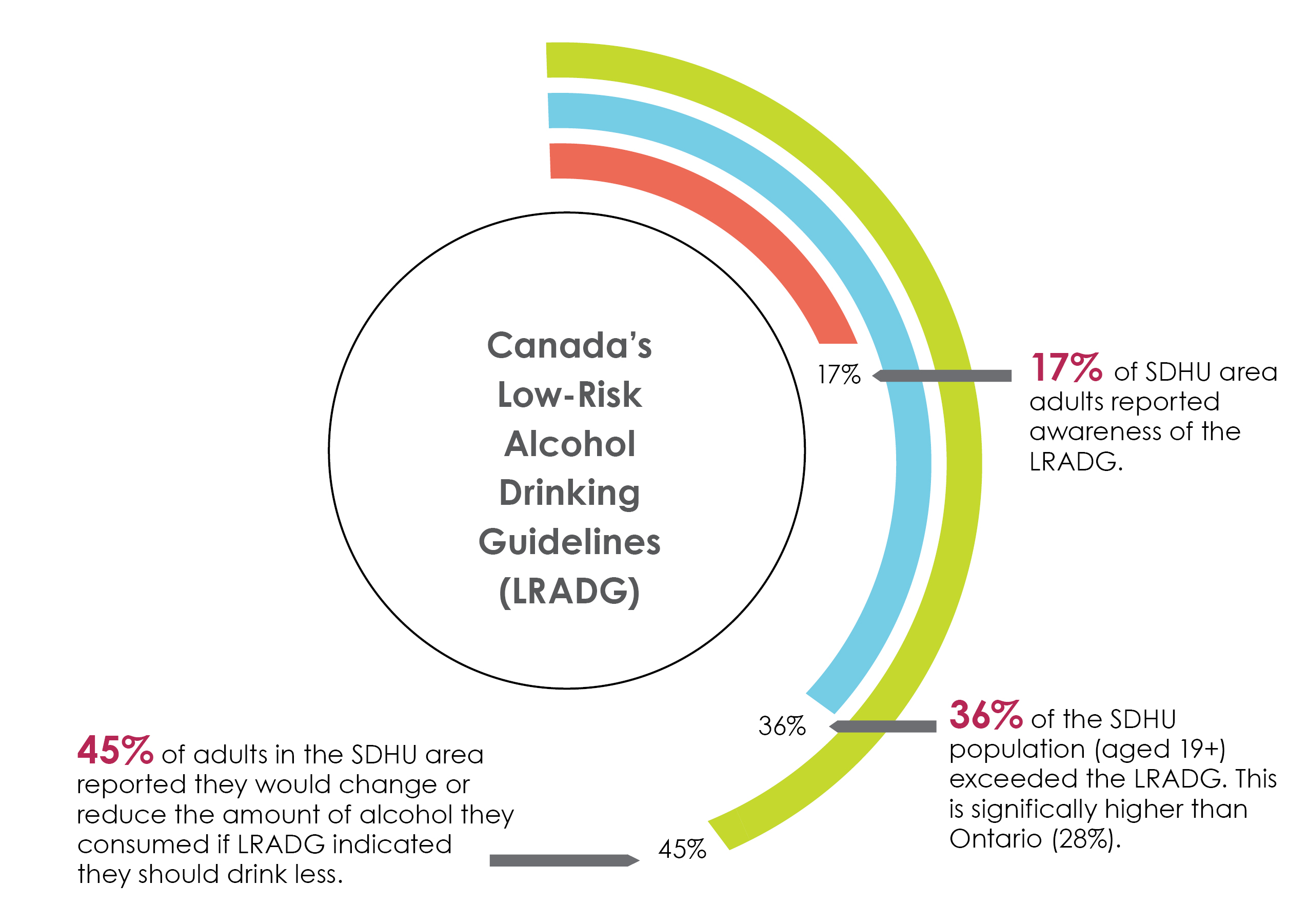

In the Sudbury & District Health Unit area, 17% of adults reported awareness of Canada’s Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines. Thirty-six percent exceeded these guidelines, which is significantly higher than Ontario. Forty-five percent reported they would change or reduce the amount of alcohol they consumed if the guidelines indicated they should drink less.

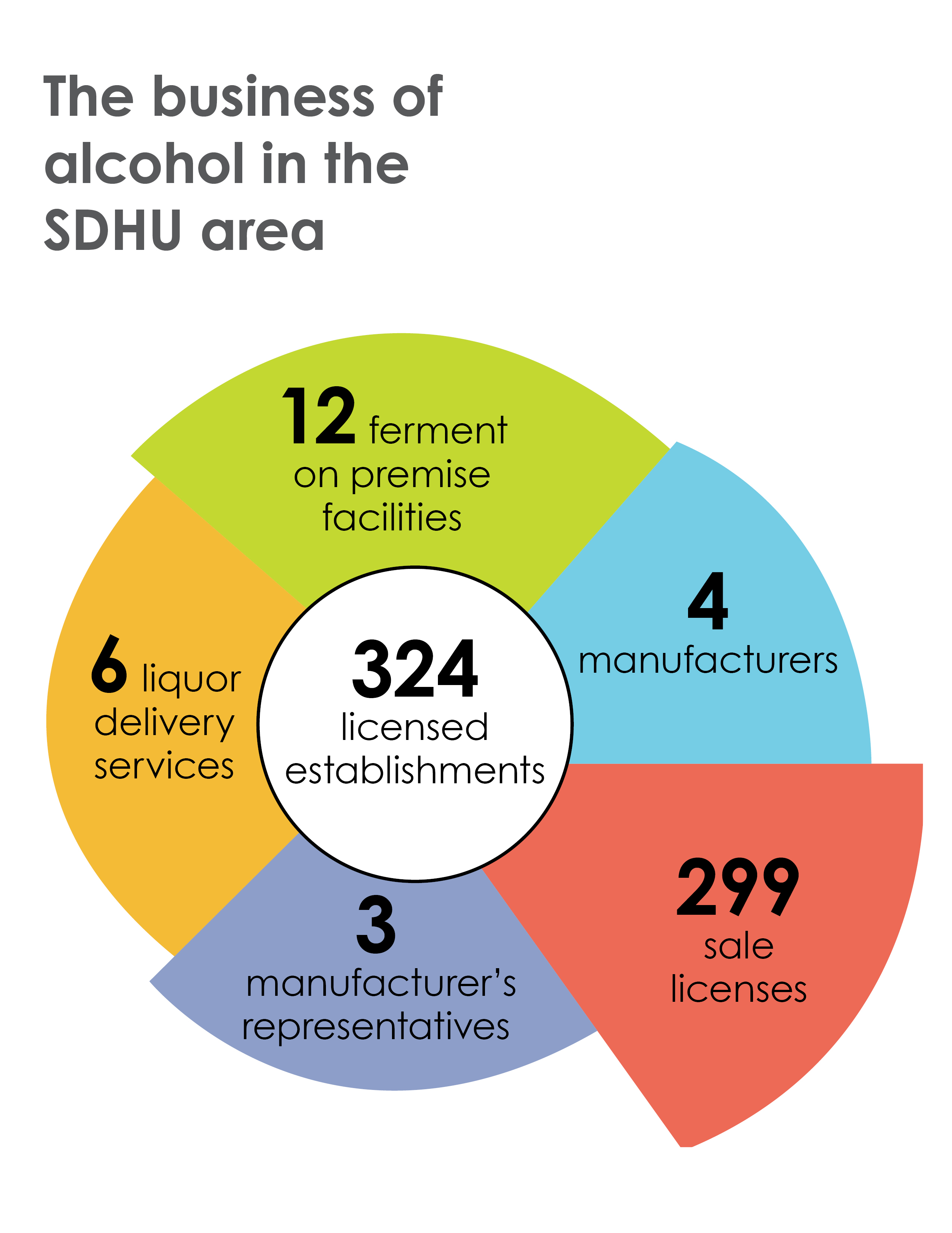

There are a total of 324 licensed establishments in the Sudbury & District Health Unit area. Specifically, there are 12 ferment on premise facilities, 4 manufacturers, 299 sale licenses, 3 manufacturer’s representatives and 6 liquor delivery services.

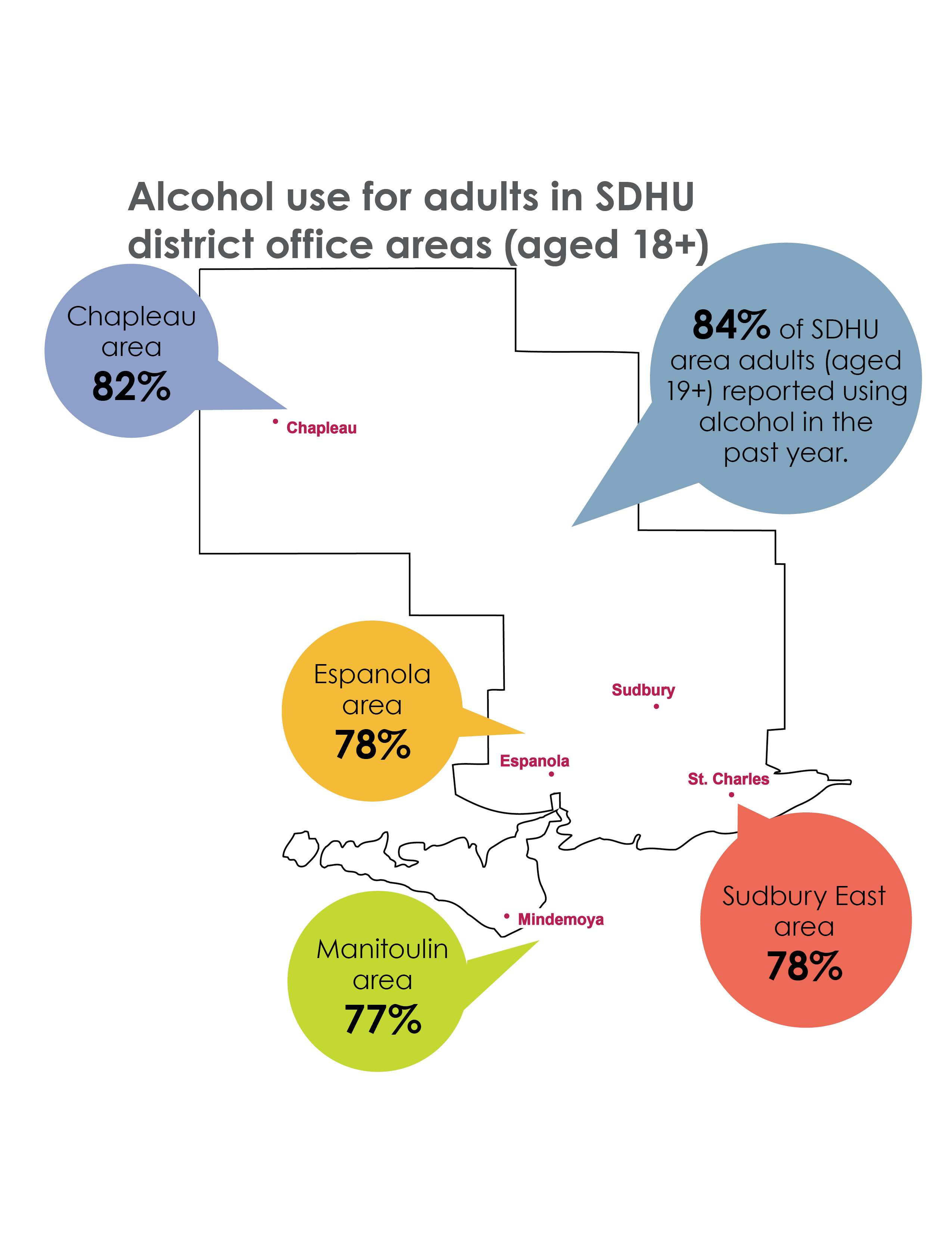

Alcohol use for adults in SDHU district office areas (aged 18+)

Map shows the percentage of adults in the Sudbury & District Health Unit areas who reported using alcohol in the past year: 82% in Chapleau, 78% in Espanola, 77% in Manitoulin, and 78% in Sudbury East. Overall, 84% of SDHU area adults used alcohol in the past year.

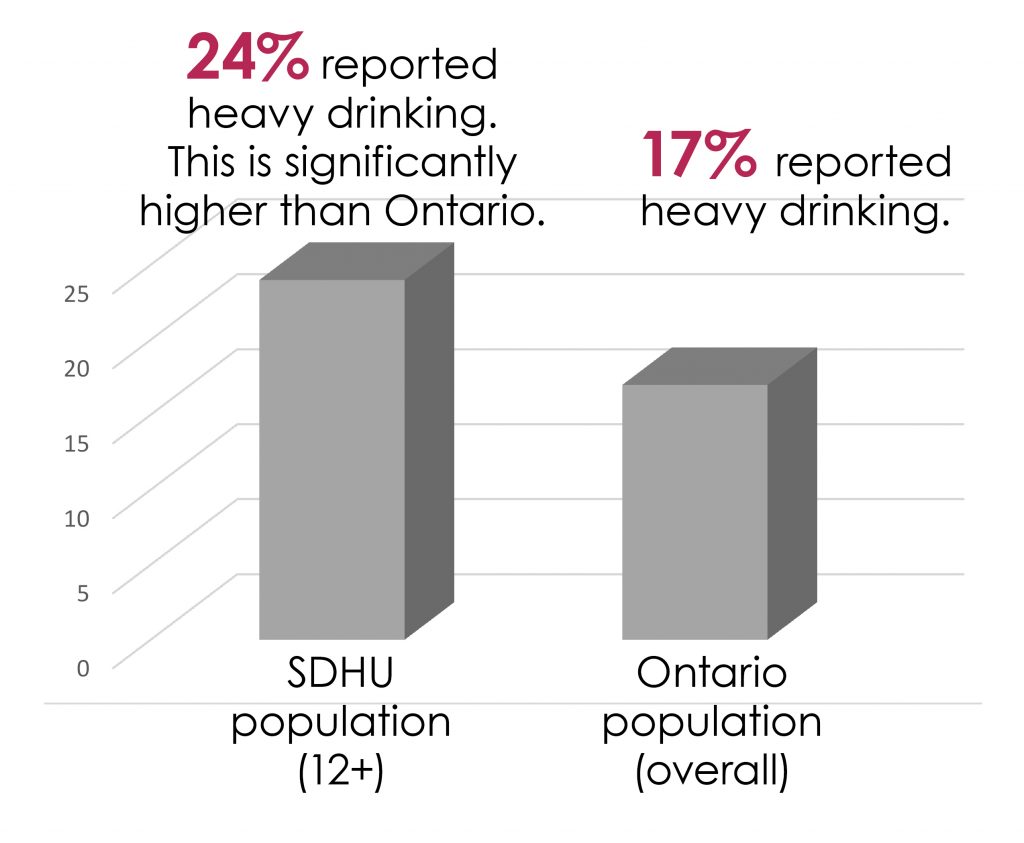

Heavy drinking is defined as consuming at least 4 or more servings of alcohol for women and 5 or more servings of alcohol for men, on at least one occasion per month in the past year.

Bar graph shows a comparison of heavy drinking rates between the SDHU population (12 years and older) and Ontario’s overall population. Twenty four percent of the SDHU population reported heavy drinking, which is significantly higher than Ontario where 17% of the population reported heavy drinking.

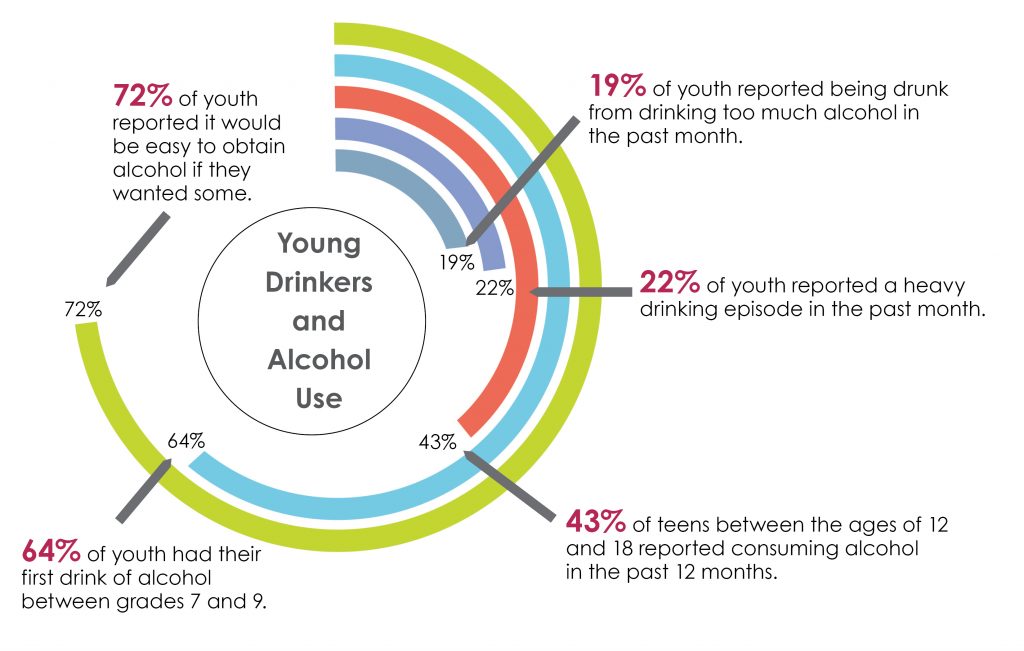

Young drinkers

Diagram shows the trends in alcohol use amongst young drinkers. Forty-three percent of teens between the ages of 12 and 18 reported consuming alcohol in the past 12 months. Nineteen percent of youth reported being drunk from drinking too much alcohol in the past month. Twenty-two percent reported a heavy drinking episode in the past month. Sixty-four percent had their first drink of alcohol between grades 7 and 9. Seventy-two percent reported it would be easy to obtain alcohol if they wanted some.

Post-secondary population

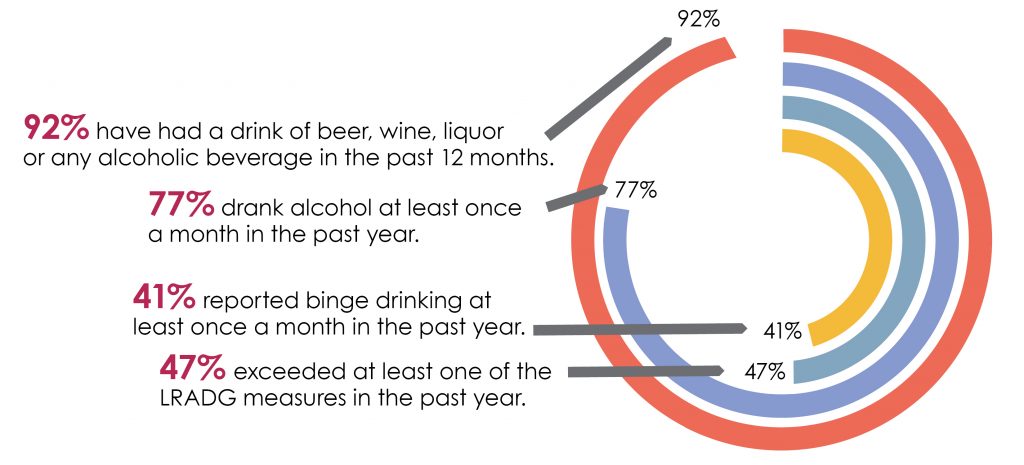

Of those who reported having consumed alcohol:

Diagram shows the trends in alcohol use amongst post-secondary students in the City of Greater Sudbury. Of those who reported having consumed alcohol, ninety-two percent have had a drink of beer, wine, liquor or any alcohol beverage. Seventy-seven percent drank alcohol at least once a month. Forty-one percent reported binge drinking at least once a month. Forty-seven percent exceeded at least one of the low-risk alcohol drinking guideline measures.

Alcohol prevention strategies are complex and multi-faceted. The aforementioned evidence is important to inform the need for and development of policies, programs, and additional resources and services in our communities to decrease alcohol-related harms.

Infographic is based on the following reports and data sources: Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario (AGCO)(2015); Butt et al (2011); Charbonneau et al. (2014); Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey (OSDUHS); SDHU (2013); Rapid Risk Factor Surveillance System (RRFSS); SDHU (2012/2013/2014); Statistics Canada, Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS)(2011/2012)

The Sudbury & District Health Unit Alcohol and the Health of Our Community – Full Report

Authors

Stephanie Bale, Health Promoter, Sudbury & District Health Unit

Eric Paquette, Public Health Nurse, Sudbury & District Health Unit

Evan Jolicoeur, Public Health Nurse, Sudbury & District Health Unit

Brenda Stankiewicz, Public Health Nurse, Sudbury & District Health Unit

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Kate Denomme, Nastassia McNair, Martha Andrews, Nicole Frappier, RRED, and The Family Health Team for their valuable feedback on this report. Thank you also to Nastassia McNair, John Tuinema, and the Communications Team for their careful review of this report, and to Jessica Bastelak for its formatting.

Contact for More Information

Mary Ann Diosi, Manager

Workplace Health and Substance Misuse Prevention

Sudbury & District Health Unit

1300 Paris Street

Sudbury, ON P3E 3A3

Telephone: 705.522.9200, ext. 341

Email: diosim@sdhu.com

Citation

Sudbury & District Health Unit. (2015). Alcohol use and the health of our community. Sudbury, ON: Author.

This report is available online at www.sdhu.com.

Ce rapport est disponible en français.

Copyright

This resource may be reproduced, for educational purposes, on the condition that full credit is given to the Sudbury & District Health Unit. This resource may not be reproduced or used for revenue generation purposes.

© Sudbury & District Health Unit, 2015

Introduction

Overview

Alcohol. As one of the oldest drugs with a long, deep rooted presence within societies, it is used by diverse cultures and people around the world. In western society, alcohol is consumed and incorporated as a societal norm. The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes that “preventing and reducing the harmful use of alcohol is a public health priority”, and as such, has committed to reducing the health and social burden of alcohol (WHO, 2014, p. 2). The burden of alcohol-related disease and death around the world is significant (WHO, 1992). Alcohol use is causally linked to over 200 diseases and injuries (WHO, 1992), and the negative health effects far outweigh any potential benefits (Canadian Public Health Association, [CPHA] 2011). Despite the expansive social, health and economic burden of alcohol misuse, the concerns surrounding alcohol use have remained a low priority in the public domain, including public policy and government decision making.

Under the Ontario Public Health Standards (OPHS) (Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, 2015), the Sudbury & District Health Unit (SDHU) is mandated to provide current and reliable data and evidence around the health effects of alcohol misuse. This evidence is pivotal to inform the need for and the development of policies, programs and additional resources and services in our communities.

A snapshot of alcohol use and misuse in our community and of harms related to its use is needed to inform and address issues related to increased alcohol consumption. The data gathered in this report will be used to address these issues in an effort to decrease alcohol-related harms from disease and injury. Using a multi-faceted approach, the SDHU seeks to develop community-based strategies to address alcohol misuse, specifically within the SDHU service area. This report will explore trends in alcohol use in our community in addition to the social, economic, and health impacts of alcohol use and misuse.

Data & Methods

The SDHU monitors alcohol consumption trends, and other alcohol use behaviours in the community through a number of data sources. The data presented within this report were obtained from the following sources:

- Rapid Risk Factor Surveillance System (RRFSS)

- Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS)

- Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey (OSDUHS)

- Statistics Canada, Census & National Household Survey (NHS)

Background

Alcohol is perceived by many to be a relatively safe beverage that is culturally and socially accepted. While, alcohol was once symbolically and culturally significant, it is now used primarily for socialization, celebration, and at times, to cope with internal and external stressors. While many are aware of the effects of impaired driving, less is known and spoken of its short and long-term health effects (Babor et al., 2010). Alcohol is metabolized in the liver and becomes acetaldehyde, a Group 1 carcinogen. Acetaldehyde is known to cause cancer (International Agency for Research on Cancer [IARC], 2015). Other examples of Group 1 carcinogens include: arsenic, asbestos, mustard gas, plutonium, radon and tobacco (IARC, 2015). In addition to its cancer causing properties, alcohol can also lead to numerous other medical and social issues, including motor vehicle collisions, violence, acute organ damage, and dependence (Babor et al., 2010).

In Canada, the majority (76%) of the population have consumed alcohol in the past year (Health Canada, 2011), and Canadians consume 50% more alcohol than the worldwide average (Shield, Rylett, Gmel, Gmel, Kehoe-Cham & Rehm, 2013).

Although alcohol can negatively impact health and social well-being, it also has an effect on the economy through the generation of revenue from production and distribution, the creation of employment opportunities and the generation of significant tax revenue for the government (Babor et al., 2010). Total direct net revenue to provincial and territorial governments from the control and sale of alcohol was $5.87 billion across Canada in

2010-2011 (Statistics Canada, 2012), and $2.8 billion in Ontario. Although this is a significant amount, the direct and indirect costs of alcohol use far exceed it (Thomas, 2012). The impacts of alcohol use and misuse are costing the government more through enforcement, healthcare, and lost productivity (Thomas, 2012). In Ontario, in 2002, a deficit of over $456 million was directly related to alcohol use (acute care, enforcement and prevention). The indirect costs of alcohol in Canada in 2002 were estimated at over $7 billion (Thomas, 2012).

The Business of Alcohol

In Canada, the provincial governments play a dual role as a distributer and regulator of beverage alcohol. Ontario has a mix of public and private systems, meaning there is involvement of both private and public outlets in the distribution of alcohol. The alcohol distribution landscape is mixed across the country, with some provinces having government monopolies, others having a mixed framework and Alberta is systemically private (Thomas, 2012).

The alcohol industry worldwide has significant influence on public policy through the lobbying of politicians and government officials, and over the last few years there has been an increasing amount of privatization of the alcohol distribution and retail system (Giesbrecht et al., 2013). The Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario (AGCO)’s 2013 Regulatory Modernization of Ontario’s Beverage Alcohol Industry, proposed many initiatives that have relaxed government regulations and plan to further liberalize the sale, service and distribution of alcohol in Ontario (AGCO, 2014). Most recently privatization of the beverage alcohol industry in Ontario allows large retail supermarkets to acquire licenses to sell beer in their facilities. In addition, a two year pilot program allows the sale of Vintners Quality Alliance (VQA) products at local Farmer’s Markets. This is of concern for public health, as evidence has shown that as availability increases, consumption increases, and with it associated harms (Babor et al., 2010).

In 2013-2014, in Ontario, there were 17 118 liquor sales licensed establishments, 577 ferment on premise facilities, 295 liquor delivery services, 358 manufacturers, and 874 manufacturer’s representatives, for a total of 19 222 licensed establishments. There were also 61 463 special occasion permits issued (AGCO, 2014). In the SDHU service area, there are currently 299 sale licenses, 12 ferment on premise facilities, 6 liquor delivery services, 4 manufacturers, and 3 manufacturer’s representatives, for a total of 324 licensed establishments (AGCO, personal communication, July 25, 2015).

The price of alcohol plays a significant role in alcohol use and misuse and pricing policies can contribute to a reduction in consumption. The Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO) pricing policy strives to balance social responsibility, excellent customer service, and profit generation while ensuring it meets the legislated requirements under the Liquor Control Act. The minimum price a product can be sold is in accordance with the three year average Consumer Price Index (Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2012-2015), which is not necessarily the practice of private sector retailers (LCBO, 2015). In 2013-2014, approximately $20.5 billion dollars’ worth of alcoholic beverages were sold in Canada, a 2.2% increase from the previous years (Statistics Canada, 2015).

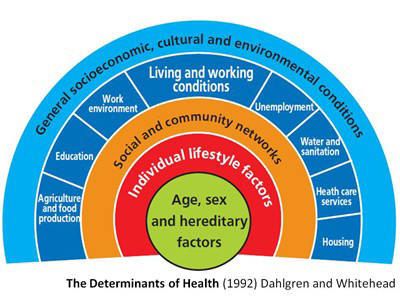

Alcohol & Income

The social determinants of health are the social, economic and environmental factors that influence a person’s health. These determinants impact an individual’s ability to access healthy foods, participate in physical activity, connect with supportive resources or services, and may reduce opportunities for good mental, physical, and spiritual health (SDHU, 2013). The use and misuse of alcohol is important once viewed with a social determinants of health lens.

A recent report by the SDHU explored the relationship between the social and economic environments and a number of health outcomes and behaviours, most notably heavy alcohol use. The report did not find a statistically significant difference for heavy drinking between the most and least deprived areas in the community, but evidence has shown that a lower socioeconomic status can contribute to increasingly negative impacts of alcohol use (SDHU, 2013; Grittner, Kuntsche, Graham, & Bloomfield, 2012). Individuals and communities with limited access to resources, lack the protective factors needed to manage alcohol misuse or dependence or related stressors (Grittner et al., 2012). The literature suggests that there is no dominant risk factor for alcohol misuse but the likelihood that a person develops an alcohol use disorder increases as the amount of inequities increases (Schmidt, Makela, Rehn, & Room, 2010). In addition, individuals within the lower socioeconomic status appear to be at an increased risk of experiencing the consequences of alcohol consumption (Grittner et al., 2012). A low socioeconomic status has been found to lead to a higher burden of disease attributable to alcohol consumption despite lower consumption rates (Schmidt et al., 2010). Probst, Roerecke, Behrendt, and Rehm (2015) examined alcohol attributable death, and found an increased risk of death among both lower income compared to high income males and females (4.87 and 4.78 greater risk, respectively).

This relationship between alcohol and conditions of inequity is complex (CPHA, 2011). Not only can socioeconomic status lead to differences in consumption and burden of disease related to alcohol, but alcohol-attributable disease can also lead to social and economic consequences (WHO, 2014). Some of these include employment related issues such as loss of earnings, increased sick days, unemployment, family and relational issues, interpersonal violence and stigmatization. The amount of alcohol consumed is not the only factor influencing the health outcomes of the population or the related socioeconomic consequences, but importantly enough so too are the patterns of consumption over time and the quality and type of alcohol consumed (Schmidt et al., 2010).

When considering the impacts of alcohol at the individual, community, and societal levels, it is necessary to consider the influence of the social determinants of health. The social determinants provide a common understanding for the development of strategies, policies, programs, services, supports or initiatives aimed at addressing the issue of alcohol misuse across the socioeconomic gradient.

Alcohol Consumption in the Sudbury & District Unit Area

Demographic Data

The SDHU service area includes a population of 192 291 and covers over 46 000 square kilometres. The main office is located in Greater Sudbury, and four district offices are located in the following communities: Manitoulin (Mindemoya), Espanola, Sudbury East (St. Charles), and Chapleau. Each district office area comprises demographic variances, for example, age distribution, Aboriginal status, and health needs, to which services are tailored to meet the individual needs of the community (see Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1: Population, by Age, Sex, Aboriginal Status, & Census Division, 2011.

| Geographic Area | Population | Aboriginal Status | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greater Sudbury* | 160 380 | 13 045 (8.1%) | 48.8% | 51.2% |

| Manitoulin District* | 13 048 | 5 295 (40.5%) | 50.0% | 50.0% |

| Sudbury District* | 21 200 | 3 334 (15.7%) | 50.8% | 49.2% |

*Greater Sudbury census division includes Greater Sudbury Census Subdivision and the Wahnapitae 11 First Nation Subdivision. The Sudbury Census Division comprises 86% of the SDHU land area including but not limited to the Chapleau, Espanola, and Sudbury East area. The Manitoulin Census Division comprises all municipalities, reserves, and townships on the island.

Table 2: Population, by Sex, & District Office Area, 2011.

| Geographic Area | Population | Male | Female | 0-18 years of age | 19-44 years of age | 45+ years of age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chapleau Area | 2 503 | 49.8% | 50.2% | 23.1% | 28.4% | 48.6% |

| Espanola Area | 9 467 | 49.9% | 50.1% | 21.3% | 26.9% | 51.7% |

| Manitoulin Area | 13 048 | 50.0% | 50.0% | 22.3% | 25.4% | 52.2% |

| Sudbury East Area | 6 526 | 52.3% | 47.7% | 16.2% | 24.2% | 59.6% |

Alcohol Use in Our Communities

Alcohol Use

The majority (84%) of SDHU area adults (aged 19+) reported consuming alcohol in the past 12 months. This is significantly higher than Ontario (78%) (Statistics Canada, 2011-2012).

In Greater Sudbury, 84% of adults (aged 18+) reported consuming alcohol in the past year. This is significantly higher than Espanola and Manitoulin areas (RRFSS, 2012). See Table 3 for a full breakdown.

Table 3: Alcohol Use, by District Office Area, 2012.

| Geographic Areas | Alcohol Use |

|---|---|

| Greater Sudbury | 84.4% |

| Espanola Area | 77.9%* |

| Manitoulin Area | 77.2%* |

| Sudbury East Area | 77.6% |

| Chapleau Area | 81.5% |

Heavy Drinking

Heavy drinking is defined as consuming four (female) and five (male) or more alcoholic beverages on at least one occasion per month in the past year. In the SDHU area, nearly a quarter (24%) of adults (aged 12+) reported heavy drinking. This is significantly higher than Ontario (17%), and has not risen significantly since 2005 (19%) (Statistics Canada, 2013-2014).

Low-Risk Drinkers

Canada’s Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines (LRADG) were developed by a group of experts on behalf of the National Alcohol Strategy Advisory Committee (NASAC) and were informed by the report, Alcohol and health in Canada: A summary of evidence and guidelines for low risk drinking (Butt et al., 2011). The guidelines were developed to moderate alcohol consumption and reduce the harms associated with acute and chronic alcohol use. In 2013-2014, 36% of the SDHU population (aged 19+) exceeded the LRADG5, which significantly higher than Ontario (28%) (Statistics Canada, 2013-2014).

In the SDHU area, only 17% of adults reported awareness of Canada’s LRADG. Nearly half (45%) reported they would change or reduce the amount of alcohol they consumed if the LRADG indicated they should drink less (RRFSS, 2013). Similar results were observed in the Campus Alcohol Behaviour Survey conducted in 2013 in Greater Sudbury. These results are further explained in the section Alcohol and Youth.

When asked to identify the maximum number of alcoholic beverages according to the LRADG, most of SDHU area adult men (66%) and women (75%) underestimated the weekly limits (RRFSS, 2013).

In Greater Sudbury, 20% of adults had seen or heard about Canada’s LRADG, and nearly half (46%) reported they would change or reduce the amount of alcohol they consumed as a result of the LRADG (RRFSS, 2001-2010).

Table 4: Awareness of LRADG, by District Office Area, 2001-2010.

| Indicator | Greater Sudbury | Sudbury East | Chapleau | Espanola | Manitoulin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of adults (aged 18+) who have seen or heard about Canada’s Low Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines (LRADG) | 19.8% | 20.6% † | - | 16.4% † | 10.0% †* |

| Percentage of adults (aged 18+) who would change (reduce) the amount of alcohol they consumed because of the LRADG | 46.0% | 66.7%* | - | 43.3% † | 61.3%* |

†Interpret with caution — high sampling variability.

Young Drinkers

Alcohol use is a common practice among youth and young adults in our communities. Over half (54%) of teens between the ages of 12 and 18 reported consuming alcohol in the past 12 months, and nearly half (43%) of youth (aged 12 to 18 years) reported heavy drinking (Statistics Canada, 2013-2014). Nearly two-thirds (64%) of youth in the SDHU area initiated drinking between grade 7 and 9; 19% reported being drunk3 in the past month; and 72% reported it was easy to obtain alcohol (Boak, Hamilton, Adlaf, & Mann, 2013).

Among our post-secondary population, the majority (92%) have used alcohol in the previous 12 months. Students between the ages of 19 and 24 were least likely to abstain from alcohol, whereas those with a high academic average, non-Caucasian, or those who had been pregnant or breastfed were most likely to abstain. Of those who reported consumption of alcohol, most (77%) consumed at least monthly, and just over half (53%) reported getting drunk3 at least monthly. Forty-one percent of students reported binge drinking4 at least once a month in the past year, and 46% reported exceeding at least one of the LRADG measures5 in the past year (Charbonneau et al., 2014).

Less than a fifth (15%) of the post-secondary students in Greater Sudbury were aware of the LRADG; this did not seem to affect binge drinking or drinking over the daily LRADG. However, awareness of the LRADG contributed to fewer binge drinking episodes, a reduction in the rates of drunkenness and use in excess of the weekly limits (this was diminished by personal characteristics, such as age) (Charbonneau et al., 2014).

Health Impacts of Alcohol Consumption

Worldwide, the use and misuse of alcohol contributes to over 200 acute and chronic illnesses and injuries (WHO, 1992), and is one of the top five risk factors for disease, disability, and death (Lim et al., 2012). Globally, alcohol is estimated to cause 3.3 million deaths each year, which accounts for 6% of all deaths (WHO, 2015). In Ontario, only tobacco rates higher for substance-attributable morbidity and mortality (Ratnasingham et al., 2013). Alcohol, as a risk factor for health, is linked to many different types of cancer, cardiovascular disease, gastro-intestinal disease, injury, and can impact sexual health, and pre and post-natal health.

Awareness of the link between daily alcohol consumption and selected chronic disease in the SDHU service area is quite high, with the exception of cancer. Most adults in the SDHU area were aware that alcohol is causally linked to the following diseases: Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) (97%), liver or stomach disease (96%), depression (90%), diabetes (80%), heart disease and stroke (79%). Fewer than half (48%) were aware that alcohol can increase a person’s risk of developing cancer (RRFSS, 2012).

Most adults in the Greater Sudbury area were aware that consumption of alcohol is causally linked to heart disease and stroke (78%), depression (90%), diabetes (80%), liver stomach disease (96%), and FASD (97%). Fewer than half (49%) were aware of the increased risk of cancer with daily consumption of alcohol (RRFSS, 2001-2010). See Table 5 for a full breakdown by district office areas.

Table 5: Awareness of alcohol use and chronic disease incidence, by district office area, 2012.

| Indicator | Greater Sudbury € | Sudbury East | Chapleau | Espanola | Manitoulin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of adults (aged 18+) who have heard that drinking alcohol everyday may increase the risk of cancer. | 49.1% | 48.6% | - | 49.2% | 37.5%* |

| Percentage of adults (aged 18+) who believe that drinking alcohol causes heart disease and stroke. | 77.7% | 83.3% | 86.1% | 74.3% | 74.7% |

| Percentage of adults (aged 18+) who believe that drinking alcohol causes depression. | 90.0% | 94.8% | 90.7% | 88.7% | 91.3% |

| Percentage of adults (aged 18+) who believe that drinking alcohol causes diabetes. | 80.3% | 85.4% | 69.4% | 79.0% | 80.0% |

| Percentage of adults (aged 18+) who believe that drinking alcohol causes disease of the liver/stomach | 95.8% | 99.0%* | 95.4% | 95.7% | 96.1% |

| Percentage of adults (aged 18+) who believe that drinking alcohol causes FASD. | 97.1% | 93.8% | 94.9% | 97.3% | 97.6% |

*Significantly different from Greater Sudbury.

€ Reference Group

Alcohol and Cancer

Unlike many other health risks associated with alcohol use and misuse, few recognize the link between alcohol use and cancer. Alcohol, considered a class 1 carcinogen (IARC, 2015), which is an important cause of cancer in humans (Cogliano et al., 2011). The use of beverage alcohol, as little as one drink a day on average, can put an individual at risk of developing breast, colon, rectum, esophagus, larynx, liver, mouth, and pharynx cancer (Rehm, Sempos, & Trevisan, 2003a; Rehm, Greenfield, & Kerr, 2006b). In 2010 in Ontario, approximately 2% or 1000 new cancer cases can be attributed to alcohol, and if we adjust that number to account for underestimation of alcohol consumption, this number could increase to nearly 4% or 3000 cases (Cancer Care Ontario, 2014). The highest percentage of cases are cancers of the upper digestive tract (e.g., oral, pharyngeal, and laryngeal cancer). Due to the higher consumption of alcohol among males, a larger proportion of cancer cases in males are attributable to alcohol compared to females (10-29% vs. 3-8%) (Cancer Care Ontario, 2014). Approximately 2%-7% of breast cancer cases can be attributed to alcohol use. Colorectal cancer represents close to 40% of all alcohol-attributable cases (Canadian Cancer Society’s Steering Committee on Cancer Statistics, 2013). See table 6 through 8 for additional details.

Alcohol and Chronic Disease

Alcohol use is linked to a number of chronic diseases. Although a moderate amount of alcohol may have some protective effects for type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and ischaemic heart disease, the many other health effects may in fact negate the positive effects (Baliunas et al., 2009; Roerecke & Rehm, 2012). When interpreting research it is important to remember that people often underestimate their alcohol consumption by amounts of 30 to 70% (Babor et al., 2010), which could in turn underestimate the magnitude of risk.

Butt, et al. (2011) summarized the increased risk of serious medical conditions by average standard drinks per day. For example, consumption of one drink per day can increase an individual’s risk of liver cancer by 10%, death by liver cirrhosis in women by 139%, and hypertension in men by 13%. See Table 6 through 8 for a full breakdown for both men and women.

Table 6. Percentage change in long-term relative risk by average standard drinks per day for 5 illnesses that are similar for men and women aged below 70 years.

| Type of Illness or Disease | 1 Drink | 2 Drinks | 3-4 Drinks | 5-6 Drinks | +6 Drinks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral Cavity & Pharynx Cancer | +42% | +96% | +197% | +366% | +697% |

| Oral Esophagus Cancer | +20% | +43% | +87% | +164% | +367% |

| Colon Cancer | +3% | +5% | +9% | +15% | +26% |

| Rectum Cancer | +5% | +10% | +18% | +30% | +53% |

| Liver Cancer | +10% | +21% | +38% | +60% | +99% |

Source: Butt et al. (2011)

Table 7. Percentage change in long-term relative risk by average standard drinks per day for 5 illnesses for men aged below 70 years.

| Type of Illness or Disease | 1 Drink | 2 Drinks | 3-4 Drinks | 5-6 Drinks | +6 Drinks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemorrhagic Stroke (morbidity) | +11% | +23% | +44% | +78% | +156% |

| Hemorrhagic Stroke (mortality) | +20% | +21% | +39% | +68% | +133% |

| Ischemic Stroke (morbidity) | -13% | 0% | 0% | +25% | +63% |

| Ischemic Stroke (mortality) | -13% | 0% | +6% | +29% | +70% |

| Hypertension | +13% | +28% | +54% | +97% | +203% |

Table 8. Percentage change in long-term relative risk by average standard drinks per day for 6 illnesses for women aged below 70 years.

| Type of Illness or Disease | 1 Drink | 2 Drinks | 3-4 Drinks | 5-6 Drinks | +6 Drinks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | +13% | +27% | +52% | +93% | +193% |

| Hemorrhagic Stroke (morbidity) | -29% | 0% | 0% | +76% | +249% |

| Hemorrhagic Stroke (mortality) | +22% | +49% | +101% | 199% | +502% |

| Ischemic Stroke (morbidity) | -18% | -13% | 0% | +31% | +121% |

| Ischemic Stroke (mortality) | -34% | -25% | 0 | +86% | +297% |

| Hypertension | 0% | +48% | +161% | +417% | +1414% |

Alcohol and Mental Health

Depression, anxiety and other mental illnesses have been linked to alcohol use. In some cases alcohol use may contribute to the development and severity of a mental illness, or may cause a mental illness (Boden & Fergusson, 2011). Research suggests that there is a causal linkage between alcohol use disorders and major depression, and that increased use of alcohol increases the risk of depression (Boden & Fergusson, 2011).

In Ontario, mental health and addictions contributed to over 600 000 health adjusted life years6 lost, with alcohol use disorders accounting for more than 80 000. Alcohol use disorders contributed to the greatest number of deaths (88%) and highest percentage of years of life lost (91%) compared to other mental illnesses and addictions (Ratnasingham et al., 2013).

Substance use disorders were highest among youth (12%) and lowest among adults aged 45+ (2%). Males had higher rates of substance use disorders compared to females, in the past 12 months (6% vs. 3%). Approximately 5% of males and 2% of females met the criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence in the past year (Statistics Canada, 2012).

Alcohol and Injury

Impaired Driving

Alcohol use affects reasoning and perception, and decreases reaction time, therefore as alcohol consumption increases, the risk of alcohol-related injuries increases (Blomberg, Peck, Moskowitz, Burns, & Fiorentino, 2009).

Although impaired driving fatalities have declined since 1993, in 2012, there were 143 fatalities on Ontario roads, 25% of which were due to impaired driving (Ministry of Transportation, 2012). In 2014, in Greater Sudbury, there were 164 impaired driving offences, 33 of which were female. Also in 2014, 16 132 vehicles were checked by the Reduce Impaired Driving Everywhere (R.I.D.E.) program, and of those 28 received suspensions and 20 were charged with a blood alcohol concentration above 0.08 (Greater Sudbury Police Service, 2014).

Novice drivers and those 21 years of age and under, cannot have any alcohol in their bloodstream while driving. In Greater Sudbury, 15 drivers under the age of 21 were charged with impaired driving (Greater Sudbury Police Service, 2014).

In the SDHU area, 6%7 of drivers (aged 16+) reported having driven a motor vehicle after 2 or more drinks the hour before they drove, and a slightly higher percentage (9%) of SDHU area respondents (aged 12+) reported being a passenger in a motor vehicle where the driver had consumed alcohol. Similar results were observed provincially (6% and 9% respectively) (Statistics Canada, 2009-10).

Eleven percent (11%7) of SDHU area respondents (aged 12+) reported driving a recreational vehicle (ATV, snowmobile, boat, etc.) after consuming 2 or more alcoholic drinks. Similar results were observed provincially (7%). A significantly higher proportion (10%8) of SDHU area respondents (aged 12+) reported being a passenger of a recreational vehicle where the driver had consumed alcohol compared to the province (5%) (Statistics Canada, 2009-10).

Alcohol and Other Injuries

Injuries can be divided into two categories: unintentional and intentional. Unintentional injuries include road traffic injuries, drownings, burns, poisoning and falls. Intentional injuries are those that result from deliberate acts of violence against oneself or others (WHO, 2007). In Ontario, alcohol and drugs were found to be involved in nearly a quarter (23%) of motor vehicle collisions, 25% of homicides, 14% of suicides, and 7% of unintentional falls with a blood alcohol content (BAC) greater than or equal to 0.08% (Canadian Institute for Health Information [CIHI], 2007). In 2009-2010, there were 142 unintentional falls with a blood alcohol concentration greater than or equal to 0.08% (CIHI, 2011), and in Ontario in 2010, there were 89 drownings, 44% of which were related to alcohol use (Ontario Ministry of Community Safety & Correctional Services, 2011).

Alcohol, Pregnancy & Breastfeeding

Alcohol use during pregnancy should be avoided. The fetus becomes exposed to alcohol through the mother’s bloodstream, and can result in a variety of physical and developmental impairments (Public Health Agency of Canada [PHAC], 2012). The most common diagnosis is FASD, which refers to physical, mental and psychological deficits that can occur with an individual if their mother consumed alcohol during her pregnancy. These deficits can have both acute and chronic implications (Chudley, Conry, Cook, Loock, Rosales, & LeBlanc, 2005). Although there is limited evidence to confirm the quantity of alcohol that may contribute to FASD or other birth defects, alcohol use during pregnancy can contribute negatively to the health of a newborn (Foltran, Gregori, Franchin, Verduci, Giovanni, 2011). Research has found that heavy alcohol use prenatally increases risk of behavioural problems, anxiety and depression (O’Leary, Nassar, Zubrick, Kruinczuk, Stanley & Bower, 2010). It is recommended to completely abstain as no amount can be considered safe (Centre for Disease Control [CDC], 2005). The same advice can be made for alcohol consumption and breastfeeding due to potential impacts to infant sleeping patterns and behaviour with presence of alcohol in breast milk. When breastfeeding, it is recommended to store breast milk in advance to avoid the presence of alcohol in breast milk (Giglia & Binns, 2006).

SDHU area adults were asked to respond to a number of questions related to their beliefs and knowledge of the harmful effects of alcohol use during pregnancy. Most adults (82%) in Greater Sudbury reported believing that drinking alcohol during pregnancy is harmful to an unborn baby (RRFSS, 2001-2010). Similar results were observed for all four district office areas (see Table 10 for details).

Table 9: Percentage Of Adults (aged 18+) who Believe Drinking Alcohol during Pregnancy is Harmful to an Unborn Baby, SDHU, 2001-2010.

| Geographic Areas | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| Greater Sudbury € | 81.6% |

| Sudbury East Area | 76.6% |

| Chapleau Area | 80.0% |

| Espanola Area | 78.7% |

| Manitoulin Area | 84.2% |

€ Reference Group

Youth, Young Adults and Alcohol

Youth and young adults are at risk of alcohol-related harm and in particular at risk for more short-term impacts such as falls, date rape, and other assaults as well as an increased risk of injuries and deaths caused by impaired driving (CPHA, 2011). This is an increasingly vulnerable time for the developing brain. The regions of the brain responsible for various actions, such as: judgement, planning and impulse control, new learning, information transmission, rewards systems, can all be affected by the consumption of alcohol (Clark, Thatcher, & Tapert, 2008). Due to the rapid changes occurring in the brain, youth and young adults are more impacted by marketing and advertising, are more likely to expose themselves to risk taking behaviours including alcohol use, and are at an increased risk of addiction compared to adults (Pechmann, Levine, Loughlin, & Leslie, 2005). Exposure to alcohol marketing has shown to affect the perceptions of drinking, specifically around promoting and reinforcing alcohol as a seemingly positive, glamourous, and low-risk activity (Babor, et al., 2010). While this type of marketing can lead to more favorable attitudes, it also increases the normalization of acceptance towards heavy drinking (Babor, et al., 2010; Heipel-Fortin, 2007).

Changes to the physical and social environment also strongly impact alcohol use rates. These changes include increased accessibility of alcohol, on campus versus off campus housing, the demographics of the college or university, on campus policies and enforcement of policies, the “social norm” of alcohol use, and many other activities aligned with alcohol use (Wechsler & Nelson, 2008). All of these factors contribute to binge drinking, which can in turn lead to social, environmental and physical harms (Wechsler & Nelson, 2008).

It is increasingly important to reduce and limit the amount of alcohol consumed in youth. Developmental assets, for example, family support, school engagement, and adult relationships play an important role in reducing substance use among youth and young adults, and consideration and preventive efforts should include the development of these assets.

Conclusion

Conclusions and Implications for Practice

Alcohol use is a normalized common practice undertaken by the majority of the SDHU service area, which is inclusive of our district office areas. Alcohol use and misuse also has significant social, environmental, and health impacts. As part of our mandate it is important to inform the community of these factors to make informed choices when it comes to their alcohol use. The Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse conducted extensive research in the development of Canada’s Low-risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines, and part of our mandate includes informing the public of the guidelines. Most (83%) of the SDHU area are still unaware of the guidelines and just over a third (36%) exceed the guidelines, which indicates there is a need for additional dissemination. The findings support the need for SDHU to work with the community and community organizations to inform and develop strategies to reduce alcohol use and the harms associated with alcohol misuse.

Next Steps

In order to reduce the burden of alcohol use and misuse in our community, we must continue to work comprehensively on programs that address alcohol misuse but more importantly engage and commit to addressing key strategies around alcohol use and misuse with our partners and external stakeholders. Alcohol prevention strategies are complex and multi-faceted and should include dissemination of evidence-informed practice and skills training, advocacy for policy change, and partnership development. This report highlights and supports the need to develop and deliver evidence-informed research (e.g. LRADG) in innovative and engaging ways, to advocate for review and update to current bylaws and policies, and advocacy for new bylaws and policies. In order to disseminate quality information, we must continue to monitor alcohol use trends in the community and keep apprised of new, emerging and innovative research. The alcohol report to the community captures all of this and will be used to guide these next steps.

Community Discussions:

The SDHU will conduct a number of discussions in a variety of settings with communities in our services area (including district office areas) to determine community readiness, capture lived experience as they relate to alcohol, and gain support in the development of key strategies around alcohol use and misuse.

Expert Panel:

The SDHU will gather a group of leading local experts with experience in the area of alcohol. This would include experts in addiction, mental health, academia, housing, enforcement, law, and municipal sectors. The report results will be presented to the panel, and discussion will ensue around the results, next steps, and recommendations to reduce the harms associated with alcohol use and misuse.

Report Update:

The report will be updated every 3 years and shared with the community as well as internal and external stakeholders and partners. This will act as a report for future years to monitor alcohol use trends, emerging research, and policy change.

References

Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario. (2014). 2013/14 Annual Report. Retrieved from: http://www.agco.on.ca/pdfs/en/ann_rpt/2013_14Annual.pdf.

Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario. (2013). Regulatory modernization in Ontario’s beverage alcohol industry. Retrieved from: http://www.agco.on.ca/pdfs/en/Regulatory_Modernization_in_Ontarios_Beverage_Alcohol_Industry.pdf.

Babor, T., Caetano, R., Casswell, S., Edwards, G., Giesbrecht, N., Graham, K.,…Rossow, I. (2010). Alcohol. No ordinary commodity. Research and public policy (2nd edition). Oxford University Press: New York.

Baliunas, D.O., Taylor, B.J., Irving, H., Roerecke, M., Patra, J., Mohapatra, S., & Rehm, J. (2009). Alcohol as a risk factor for type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care, 32(11), 2123-32.

Blomberg, R.D., Peck, R.C., Moskowitz, H., Burns, M., & Fiorentino, D. (2009). The Long Beach/ Fort Lauderdale relative risk study. Journal of Safety Research, 40(4), 285-92.

Boak, A., Hamilton, H.A., Adlaf, E.M., & Mann, R.E. (2013). Drug use among Ontario students, 1977-2013: Detailed OSDUHS findings (Sudbury & District Health Unit). Toronto, ON: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Boden, J.M. & Fergusson, D.M. (2011). Alcohol and depression. Addiction, 106, 906-914.

Butt, P., Beirness, D., Stockwell, T., Gliksman, L., & Paradis, C. (2011). Alcohol and health in Canada: A summary of evidence and guidelines for low-risk drinking. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Centre for Substance Abuse.

Canadian Cancer Society’s Steering Committee on Cancer Statistics. (2013). Canadian cancer statistics 2013. Toronto: Canadian Cancer Society.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2011). Ontario trauma registry 2011 report: Major injury in Ontario, 2009-10 data. Toronto: Canadian Institute for Health Information. Retrieved from: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/OTR_CDS_2009_2010_Annual_Report.pdf.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2007). Ontario trauma registry report: Major injury in Ontario, 2005-2006 and 2006-2007. Toronto: Canadian Institute for Health Information.

Cancer Care Ontario. (2014). Cancer risk factors in Ontario: Alcohol. Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

Canadian Public Health Association. (2011). Too high a cost. A public health approach to alcohol policy in Canada. Ottawa, ON. Retrieved from: http://www.cpha.ca/uploads/ positions/position-paper-alcohol_e.pdf.

Centre for Disease Control. (2005). A 2005 message to women from the U.S. surgeon general: Advisory on alcohol use in pregnancy. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/documents/surgeongenbookmark.pdf.

Charbonneau, V., Gauthier, A., Martel, J., Urajnik, D., Dénommé, J., Laclé, S.,…Thistle, N. (2014). Canada’s low-risk alcohol drinking guidelines among post-secondary students. Sudbury, ON: Sudbury & District Health Unit.

Cherpitel, C.J. (2013). Focus on: The burden of alcohol use – trauma and emergency outcomes. Alcohol Res: Current Reviews, 35, 150-4.

Chudley, A.E., Conry, J., Cook, J.L., Loock, C., Rosales, T., & LeBlanc, N. (2005). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: Canadian guidelines for diagnosis. CMAJ, 172(5), S1-S21.

Clark, D.B., Thatcher, D.L., & Tapert, S.F. (2008). Alcohol, psychological dysregulation, and adolescent brain development. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 32(3), 375- 385.

Cogliano, V.J., Baan, R., Straif, K., Grosse, Y., Lauby-Secretan, B., Ghissassi, F.,…Wild, C.P. (2011). Preventable exposures associated with human cancers. Journal of National Cancer Institute, 103(24), 1927-1839.

Dahlgren G., & Whitehead, M. (1992). Policies and strategies to promote equity in health. Copenhagen: World Health Organization.

Foltran, F., Gregori, D., Franchin, L., Verduci, E., & Giovannini, M. (2011). Effect of alcohol consumption in prenatal life, childhood, and adolescence on child development. Nutr Rev., 69(11), 642-59.

Giesbrecht, N., Wettlaufer, A., April, N., Asbridge, M., Cukier, S., Mann, R.,…Vallance, K. (2013). Strategies to reduce alcohol-related harms and costs in Canada: A comparison of provincial policies. Toronto: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Giglia, R. & Binns, C. (2006). Alcohol and lactation: a systematic review. Nutrition & Dietetics, 63, 103-116.

Greater Sudbury Police Service. (2014). Personal communication: John Calluzi.

Grittner, U., Kuntsche, S., Graham, K., & Bloomfield, K. (2012). Social inequalities and gender differences in the experience of alcohol-related problems. Alcohol Alcohol, 47(5), 597-605.

Health Canada. (2011). Canadian Alcohol and Drug Use Monitoring Survey. Retrieved from http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/drugs-drogues/stat/_2011/summary-sommaire-eng.php#a7.

Heipel-Fortin, R.B., & Rempel, B. (2007). Effectiveness of alcohol advertising control policies and implications for public health practice. McMaster University Medical Journal, 4(1), 20-25.

International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). (2015). Agents classified by the IARC monographs, volumes 1-112. Retrieved from: http:/ monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Classification/ ClassificationsAlphaOrder.pdf.

Lim, S.S., Vos, T., Flaxman, A.D., Danaei, G., Shibuya, K., Adair-Rohani, H.,…Ezzati, M. (2012).

A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet, 380, 2224-60.

Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO). (2015). Pricing Policy. Retrieved from: http://www.lcbo.com/content/lcbo/en/corporate-pages/about/aboutourbusiness.html.

Macdonald, S., Greer, A., Brubacher, J., Cherpitel, C., Stockwell, T., & Zeisser, C. (2013). In: Boyle P, Boffetta P, Lowenfels AB, Burns H, Brawley O, Zatonski W et al., editors. Alcohol consumption and injury. Alcohol: science, policy and public health. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. (2015). Ontario Public Health Standards 2008. Toronto: Queen’s Printer of Ontario.

Ministry of Transportation. (2012). Ontario road safety. Annual report 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.mto.gov.on.ca/english/publications/pdfs/ontario-road-safety-annual-report-2012.pdf.

O’Leary, C.M., Nassar, N., Zubrick, S.R., Kurinczuk, J.J., Stanley, F., & Bower, C. (2010). Evidence of a complex association between dose, pattern and timing of prenatal alcohol exposure and child behaviour problems. Addiction, 105(1), 74-86.

Ontario Ministry of Community Safety & Correctional Services. (2011). Drowning review. A review of all accidental drowning deaths in Ontario from May 1 to September 30th 2010. Toronto, ON: Office of the Chief Coroner Province of Ontario. Retrieved from: http://www.mcscs.jus.gov.on.ca/stellent/groups/public/@mcscs/@www/@com/documents/webasset/ec090309.pdf.

Pechmann, C., Levine, L., Loughlin, S., & Leslie, F. (2005). Impulsive and self-conscious: Adolescents’ vulnerability to advertising and promotion. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 24(2), 202-221.

Probst, C., Roerecke, M., Behrendt, S., Rehm, J. (2015). Gender differences in socioeconomic inequality of alcohol-attributable mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Review, 34, 267–277.

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2012). The sensible guide to a healthy pregnancy. Ottawa, ON: PHAC. Retrieved from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/hp-gs/guide/assets/pdf/ hpguide-eng.pdf.

Queen’s Printer for Ontario. (2012-15). Liquor control act, R.S.O. 1990, c.L.18. Retrieved from https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/90l18.

Rapid Risk Factor Surveillance System. (2012). Sudbury & District Health Unit.

Rapid Risk Factor Surveillance System. (2013). Sudbury & District Health Unit.

Rapid Risk Factor Surveillance System. (2001-2010). Sudbury & District Health Unit.

Ratnasingham, S., Cairney, J., Manson, H., Rehm, J., Lin, E., & Kurdyak, P. (2013). The burden of mental illness and addiction in Ontario. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 58(9), 529-537.

Rehm., J., Sempos, C.T., & Trevisan, M. (2003b). Average volume of alcohol consumption, patterns of drinking and risk of coronary heart disease: A review. Journal of Cardiovascular Risk, 10(1), 15-20.

Rehm, J., Greenfield, T.K., & Kerr, W.C. (2006b). Patterns of drinking and mortality from different diseases: An overview. Contemporary Drug Problems, 33(2), 205-235.

Roerecke, M., & Rehm, J. (2012). The cardioprotective association of average alcohol consumption and ischaemic heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 107(7), 1246-60.

Schmidt, L.A., Makela, P., Rehn, J., & Room, R. (2010). Alcohol: equity and social determinants. In E. Blas & A. S. Kurup (Eds.), Equity, social determinants and public health programmes (pp. 11-29). Geneva: WHO Press.

Shield, K.D., Rylett, M., Gmel, G., Gmel, G., Kehoe-Chan, T.A., & Rehm, J. (2013). Global alcohol exposure estimates by country, territory and region for 2005—a contribution to the Comparative Risk Assessment for the 2010 Global Burden of Disease Study. Addiction, 108(5), 912-22.

Statistics Canada. (2009/10). Canadian Community Health Survey. Share File, Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

Statistics Canada. (2011). 2011 Census of Canada: Profile data for Greater Sudbury, Manitoulin, and Sudbury at the census tract level. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada

Statistics Canada. (2011/12). Canadian Community Health Survey. Share File, Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

Statistics Canada. (2012). Canadian Community Health Survey – Mental Health User Guide. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Statistics Canada. (2013/14). Canadian Community Health Survey. Share File, Ontario Ministry of Health and Long- Term Care.

Statistics Canada. (2015). The Daily: The control and sale of alcoholic beverages, for the year ending March 31, 2014. Retrieved from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/150504/ dq150504a-eng.htm.

Sudbury & District Health Unit. (2013). Opportunity for all: The path to health equity. Sudbury, ON: Author.

Thomas, G. (2012). Analysis of beverage alcohol sales in Canada. (Alcohol Price Policy Series: Report: 2). Ottawa, ON: Canadian Centre for Substance Abuse.

Wechsler, H., & Nelson, T.F. (2008). What we have learned from the Harvard Schools of Public Health College Alcohol Study: Focusing attention on college student alcohol consumption and the environmental conditions that promote it. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 69(4), 481-90.

World Health Organization. (1992). WHO Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) 10th revision. Geneva: WHO Press.

World Health Organization. (2007). Alcohol and injury in emergency departments. France: WHO. Retrieve from: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/alcohol_injury_summary.pdf.

World Health Organization. (2014). Global status report on alcohol and health 2014. Geneva: WHO Press. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112736/1/9789240692763_eng.pdf.

World Health Organization. (2015). Alcohol. Fact sheet. Retrieve from: http://www.who.int/ mediacentre/factsheets/fs349/en/.

This item was last modified on December 23, 2025