Texting and driving among youth: knowledge and strategies for prevention in Northeastern Ontario

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Determinants of texting and driving behaviour

- Effects of distracted driving

- Prevention strategies

- Summary of literature review findings

- Survey of youth on texting and driving

- Interviews

- Advertisement attention as measured by eye-movement

- Overall study conclusion

- Appendix

- References

Introduction

Research shows that cellphone use while conducting day-to-day activities such as driving, walking, and bicycling is increasingly frequent (Thumser & Stahl, 2013). Texting while driving is a factor in many motor vehicle accidents and fatalities (Lee et al., 2013). Harrison (2011) found that 91% of college-aged participants reported that they have texted while driving. Thus, the risk associated with texting and driving, particularly for young drivers, has become a public health issue.

The current research project

Although the risks of texting and driving have been demonstrated, little is known about effective approaches to changing the behaviour, particularly among youth, who may be most at risk.

In March 2015, the Evaluating Children’s Health Outcomes (ECHO) Research Centre at Laurentian University invited community partners, including Public Health Sudbury & Districts, to identify issues of local relevance that could be studied by students interested in pursuing community-relevant theses, practicums, and research projects. A research question concerning texting and driving among local youth populations was brought forward as a potential issue with community implications. Resulting from this session, a collaborative research team was developed, comprised of three staff from Public Health, two faculty members and eight students from Laurentian University.

The issue was addressed through a four-phase project examining youth perceptions of anti-texting and driving strategies, with a goal of understanding what types of messages and approaches might serve as effective deterrents to texting and driving among youth (16–24 years). The four phases included:

- A literature review of factors influencing texting and driving.

- A survey of youth to examine texting and driving perceptions, attitudes and behaviours in Northeastern Ontario rural and urban settings (Chapleau, Manitoulin Island, Lacloche Foothills, Sudbury East and Greater Sudbury).

- An eye-tracking study to determine what information in advertisements attracts youth attention.

- Interviews with local youth to learn more about the perceived effectiveness of anti-texting and driving campaigns.

This report describes the findings of all phases of the research and the implications for public health practice. All phases received research ethics approval from Public Health Sudbury & Districts and Laurentian University.

Literature review

A literature review was conducted to identify what is known about distracted driving, and in particular about the perceptions, attitudes, and behaviours of young drivers related to texting and driving.1

Method

Articles published between 2000 and 2015 were searched within four databases from different disciplines: PsycINFO, Business Source Complete, CINAHL and OVID. Two search strategies were used. First, the keywords distract*, drive*, phone and advertis* were used. A total of 150 results were obtained in PsycINFO, 399 results in Business Source Complete, 29 results in CINAHL and 1139 results in OVID. A second search was completed by broadening the analysis combining only the keywords distract*, drive* and phone. Additional sources were identified through this approach: PsycINFO provided 1 result, Business Source Complete supplied 11 results, CINAHL provided 0 results and OVID provided 2 results.

Only articles pertaining to cellphone use while driving were included. Articles were retained if they directly pertained to young drivers aged 16–24 years.

Results

Six main themes were identified in the literature review: distracted driving, texting while driving, young drivers, determinants of texting and driving behaviour, effects of distracted driving, and prevention strategies. The following sections summarize the main ideas extracted from the literature for each of these themes.

Distracted driving

Distracted driving can be defined as a shift of concentration towards a secondary task that leads to a deviation of attention, which may impact safe driving. Distracted drivers may have reduced reaction times, as well as a diminished awareness of objects in their surrounding environment such as roadway signs, traffic lights, other vehicles or pedestrians (Adeola & Gibbons, 2013; Garner, Fine, Franklin, Sattin & Stavrinos, 2015; Huang et al., 2010; Llerena, et al., 2015; Neyens & Boyle, 2007). In 2006, research conducted by the U.S.-based National Highway Traffic Safety Administration found that 78% of crashes and 65% of near-crashes in the United States were due to distracted driving (Adeola & Gibbons, 2013). In Canada, the vehicle collision damage cost each year is estimated at $62.7 billion and it is suggested that up to 90% of these crashes are caused by distracted driving (Huang et al., 2010).

Texting while driving

Texting while driving is a prevalent type of distracted driving, which has been found to cause delays in the driver’s reaction time due to dividing attention between the road and the phone (Llerena et al., 2015). This delayed reaction when individual’s text and drive has been defined as “inattention blindness”, resulting in a decrease in processing of the driver’s environmental information by up to 50% (Strayer, Drews, & Johnson, 2003). Studies have shown that texting while driving increases the likelihood of crashing by up to 23% (Wilson & Stimpson, 2010).

Young drivers

Research has indicated that texting while driving was the main factor in 21% of fatal crashes involving youth in Ontario (Tucker, Pek, Morrish, & Ruf, 2015). Young drivers (under 25 years) are more likely to use cellphones compared to other age groups: 6.7% of young drivers under the age of 25 admitted to using cellphones while driving, compared to 2.4% of older drivers (Huang et al., 2010). While this statistic does not indicate how many use cellphones specifically for texting and driving related purposes, it is possible many do use cellphones for this purpose.

Youth are the youngest and least experienced drivers on the road, resulting in a lack of critical driving experience (Mayhew, Simpson & Pak, 2003; Olsen, Lee, Simons-Morton, 2007). It is common for young drivers to mistakenly believe that they are not vulnerable to consequences of risky behaviours such as distracted driving, particularly texting and driving. This is known as the illusion of invincibility (Adeola & Gibbons, 2013). Young drivers’ willingness to engage in distracted driving seems to increase as they gain more confidence in their driving abilities, which leads to over-estimating their ability to multitask (Garner et al., 2011; Neyens & Boyle, 2008). Youth are also more likely to speed while driving (Rhodes & Pivik, 2011), as well as being most likely to engage in risk-taking and sensation-seeking behaviours (Beck, Hartos, & Simons-Morton, 2002). Studies have indicated that youth are aware that texting and driving is dangerous, but also admit that they still would text and drive if they felt it was an important call or message (Nelson, Atchley, & Little, 2009; Tucker et al., 2015).

Determinants of texting and driving behaviour

Attitudes, beliefs and social norms

According to the theory of planned behaviour, intention to use cellphones while driving, such as texting and driving, can be driven by attitudes and social norms (Hafetz, Jacobson, García-España, Curry & Winston, 2010; Struckman-Johnson, Gaster, Struckman-Johnson, Johnson & Shinagle, 2015). A major factor in the prevalence of texting and driving among young drivers may be the highly valuable social feature of cellphone use, such as the ability to organize their calendar with ease and communicating with their peers (Hafetz et al., 2010; Struckman-Johnson et al., 2015; Schlehofer, Thompson, Ting, Ostermann, Nierman & Skenderian, 2010). Hafetz et al. (2010) and Young and Lenné (2010) showed that the social value to texting while driving seemed to be a high predictor of the frequency of texting and driving among young drivers. Hafetz et al. (2010) conducted a study to evaluate young drivers’ beliefs on the advantages and disadvantages of cellphone abstention. They found that young drivers who perceive more disadvantages to abstaining from using cellphones while driving tend to engage in more frequent risky behaviours than those who perceive fewer disadvantages.

Gender and age differences

With respect to gender and age differences among youth, there is a lack of consistency in the literature. Olsen and colleagues (2013) reported that young males text and drive more than young females, but a similar study by the Canadian Association of Mental Health (CAMH) (2013) did not find any differences in texting and driving behaviours as a function of gender. Similarly, Struckman-Johnson et al. (2015) found that men and women had similar frequencies of texting and driving behaviours. According to Struckman-Johnson et al. (2015), women reported sending shorter text messages than did men. Women also rated texting and driving as more distracting than did men, and said that they would be more likely to stop texting and driving if they began to see more public health campaigns against this type of risky behaviour, such as police warnings or receiving information on the dangers. Men rated themselves to have better confidence while driving than did women.

Olsen et al. (2013) reported that older adolescents text and drive more than younger adolescents. Simons-Morton, Ouimet, Zhang, Klauer, Lee, Wang, Chen, Albert, and Dingus, (2011) examined the differences in age of passengers in affecting texting and driving behaviour in youth. Results supported that youth are less risky while driving when accompanied by an older adult compared to a peer. These results suggest that risky behaviour is considered socially acceptable among peers, influencing and increasing the probability of risky behaviour while driving with a peer.

Individual differences

Although psychosocial factors evidently have an impact on young drivers’ reported texting and driving behaviours, Schlehofer et al. (2010) argue that frequencies of cellphone use while driving may be better explained by individual differences. Three individual differences were evaluated. One factor was an overestimation of the ability to compensate for distracted driving behaviour impairments, meaning that drivers tend to rate themselves as being exceptional driver and believe the strategies they use to compensate for distraction eliminate the risk associated with texting and driving. A second individual difference is the illusion of control of their environment, which refers to drivers’ beliefs that they have better control on driving situation outcomes compared to other drivers and the illusion that they personally will not suffer impairments while texting and driving. Both of these factors (having elevated estimation of one’s ability to compensate for distracted driving behaviour impairments and a higher illusion of control) were associated with more frequent cellphone use. The third individual difference factor, the use of a “regulatory cognitive style” refers to individuals who are generally described as chronic multitaskers. Contrary to what was hypothesized, being a chronic multitasker was not associated with a higher frequency of cellphone use while driving.

Social influences

While individual differences may explain part of the variation in young drivers’ frequency to text and drive, Buckley, Chapman and Sheehan (2014) investigated social influences of parents and peers sensation seeking behaviours and risk perception on the frequency of texting and driving behaviours. Results revealed risk perception was the best predictor of the adolescents’ frequency of texting and driving. A higher perceived peer approval of the behaviour was associated with a lower risk perception. Consistent with Struckman-Johnson et al. (2015), results showed men and women both engage in texting and driving behaviours at similar frequencies. However, males generally had lower risk perception compared to females, rated themselves as more likely to engage in the behaviour and perceived more peer approval of engaging in the behaviour.

Tucker et al. (2015) surveyed Canadian adolescents, mostly Ontario residents, in hopes to determine the most common themes in distracted driving behaviours. These researchers found a correlation between the frequencies of being the distracted driver and being a passenger of a distracted driver, consistent with Buckley et al.’s (2014) hypothesis that peers have a high influence on young drivers’ decision to engage in risky driving behaviours. Tucker et al. (2015) also found that texting and driving was a strong predictor of speeding and of talking on the phone while driving, thus suggesting that these types of driving behaviours co-occur in this age group.

Effects of distracted driving

Driving simulators allow for a safe and ethical way to examine how using a cellphone affects driving performance. With the use of driving simulators, it is possible to examine specific questions about how individuals’ driving performance changes by manipulating driving tasks that would not be safe to do in real life (Amado & Ulupinar, 2005; Gaspar, et al., 2014; Hosking, Young, & Regan, 2009).

Hosking et al. (2009) used simulators to examine how young drivers’ driving performance changes when they are told to text and drive compared to when they are not. Text messaging while driving affected drivers’ visual scanning of the road, their ability to maintain time headway and lane position, and their ability to follow lane change signs. Drivers were found to look inside the vehicle as opposed to the road double the amount of time when they were distracted by a text message. This increase in time spent not viewing the road is what is hypothesized to cause a decrease in driving performance and an increase in crash risk when texting and driving. Furthermore, when texting and driving, it was found that drivers had 50% more variation in lane position and 28% more lane excursions. They were also more likely to miss traffic signs or not process them sufficiently.

Another form of technology created to allow safer communication by cellphone while driving is using voice recognition to verbally respond to text messages. Whether this conversational medium reduces the dangerous effects of texting and driving was tested by He et al. (2014) by having participants either drive a simulator alone, respond to questions by text manually or through verbal recognition. The results indicated that manual texting and driving led to longer response times, variation in lane position and gap and greater following distance, whereas verbal responding led to less severe impaired driving than manual but still affected driving performance, causing a larger standard deviation of speed and lane position condition compared to the drive-only condition. Therefore, both manual and verbal text message response affect driving behaviour, but verbal responding causes less of an impairment than manual.

Although driving simulators are useful in comparing and manipulating situations that would not be safe, ethical or legal to examine in the real world, naturalistic studies allow for an examination of how these behaviours occur in real life. Through placing cameras in participant’s cars for extended periods of time, real life observations of distracted driving behaviour can be examined. Foss and Goodwin (2014) installed driving cameras in new drivers’ cars for six months. After the videos were coded for distractions while driving, results indicated that electronics were found to be the most common distraction while driving, followed by adjusting the controls in the vehicle, and personal grooming. These distractions were found to occur less frequently with passengers. However, when there were passengers, there were more noise and horseplay distractions. These distractions were found to cause an increase in looking away from the road, leading to more dangerous driving. Similarly, Klauer et al. (2014) installed driving cameras in the cars of new drivers and more experienced drivers to record their driving behaviours over 18 months. Their results indicated that crashes or near crashes were more likely to occur when dialing a cellphone, sending or receiving a message on a cellphone and reaching for a cellphone.

Another factor that has been examined in both simulation and naturalistic driving studies is the effect of age and driving experience on the ability to handle distracting tasks while driving. Rumschlag et al. (2015) and Klauer et al. (2014) both examined differences in younger and older drivers on their ability to multitask while driving. The results of both studies indicated that younger drivers were better at multitasking and responding on a cellphone than older drivers. However, although younger drivers were better at responding on the phones while driving, both age groups had a decrease in driving performance while texting and driving. Young drivers were hypothesized to be better multitaskers at using cellphones while driving due to their confidence and common use of this technology. Tractinsky, Ram, and Shinar (2013) examined younger and older drivers’ engagement in cellphone conversations while driving in a simulator, allowing the participants some ability to decide when to initiate or answer phone calls. Results indicated that both young and old drivers were more likely to answer a call than initiate one. Younger drivers were more likely to initiate or answer calls compared to older drivers, and were found to be more confident in their ability to multitask with a cellphone while driving.

Finally, experience while driving has also been shown to affect where younger and older drivers look when texting and driving. The use of eye tracking in the driving simulator results indicated that older, more experienced drivers, looked more at the front and centre of the car, whereas, younger less experienced drivers looked more towards the dashboard area. Both age groups had impaired driving performance when texting while driving and continued to look where their age group trended to (Nabutilan, Aghazadeh, Nimbarte, Harvey & Chowdhury, 2011). Although younger drivers can handle their cellphones more efficiently while driving than older drivers, driving performance for both groups is diminished when they are texting and driving. This is particularly an issue with younger drivers, because they are more likely to text while driving, but are still just as likely to have diminished driving performance, causing them to be at high risk for crashes while driving (Klauer et al., 2014; Rumschlag et al., 2015; Tractinsky et al., 2013).

Prevention strategies

Several texting and driving prevention strategies have been suggested, such as commitment techniques, in which people make a public pledge not to text and drive (Buckley et al., 2014 Cismaru, 2014), providing education within schools (Buckley et al., 2014 Cismaru, 2014; Harrison, 2011), health and safety teachings to the public (Harrison, 2011; Huang et al., 2010; Jacobson & Gostin, 2010), the use of simulators (Buckley et al., 2014), exposing young drivers to graphic videos and pictures (Cismaru, 2014), development of new technology (Garner et al., 2011; Jacobson & Gostin, 2010), and further legal interventions (Buckley et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2010; Garner et al., 2011; Jacobson & Gostin, 2010; Harrison, 2011).

Students who participated in a six-month behaviour change program at school showed a decrease of distracted driving behaviours (Buckley et al., 2014). School-based programs may be a good way to increase safe driving behaviours and reduce texting and driving behaviours among young drivers (Buckley et al., 2014; Cismaru, 2014; Harrison, 2011). Health and safety programs for the public may also be an effective way to further educate drivers on the risks associated with using cellphones while driving (Harrison, 2011; Huang et al., 2010; Jacobson & Gostin, 2010). Simulation research directly measures distractions caused by cellphone use while driving (Buckley et al., 2014), and could be used as part of such behaviour change programs. In fact, asking individuals to engage in the risky driving behaviour while driving a simulator may be an effective way to change risk perception resulting in self-behaviour change. However, behaviour change programs should also provide individuals with possible ways to implement the behaviour change, such as suggesting to put their cellphones away where they are unable to reach it when tempted to text or talk on the phone while driving (Cismaru, 2014).

Prevention strategies should not only aim to educate on the dangers, but also consist of providing tangible solutions to drivers that will be effective in averting the threat advocated by the scare tactics. Solutions will help young drivers move away from fear responses, such as cognitive dissonance, and towards the adoption of the recommended behaviours. The higher the motivation, the more individuals will carefully consider behaviours advocated by the prevention strategies and seek to adopt the desired behaviours (Cismaru, 2014).

Summary of literature review findings

Distracted driving accounts for a high percentage of crashes and near crashes today. The findings from the literature review show that up to 90% of collisions in Canada are caused by distracted driving. These collisions are often caused by texting and driving due to delays in the driver’s reaction time. Studies have shown that texting and driving increases the likelihood of a collision by up to 23%. In 21% of fatal collisions involving Ontario youth, texting and driving has been the main factor. Young drivers are also most likely to text and drive compared to other age groups. Youth are more confident in their ability to text and drive due to their familiarity with the technology, although they are the least experienced driver’s. Verbally responding to messages decreases the likelihood of collisions compared to texting, although the driver’s performance is still affected. Effective prevention strategies identified by the literature review include school-based intervention programs, health and safety programs for the public, and simulation techniques. Prevention strategies should also provide solutions for drivers who are tempted to use their cellphones while driving.

Survey of youth on texting and driving

The aim of the study was to critically examine the opinions, perceptions and attitudes of youth in Northeastern Ontario in regard to texting and driving as well as examine possible factors that may prevent youth from engaging in this behaviour. The current study examined self-reported texting and driving behaviours and perceptions of youth between the ages of 16–24 year olds. The goal of the current study was to examine where, when, and under what specific situations youth are most likely to engage in texting and driving behaviour. Furthermore, as there is little research on how aware youth are regarding the consequences of texting and driving, they were asked about these consequences. Finally, participants were asked about the possible prevention strategies in an effort to understand what would lead them to stop engaging in texting and driving behaviour.

Method

Participants were recruited through the use of public posters, and through online recruitment using posts on social media. The final sample consisted of 215 participants (164 females, 51 males) between the ages of 16–24 years who had a valid driver’s license and lived in Ontario. Of these, 205 participants identified as speaking English as their primary language, and 10 identified as speaking French.

Data were collected online through Fluid Surveys. The survey evaluated youth’s self-reported texting and driving behaviour, where and when the behaviour occurs, their perceptions about the behaviour and opinions about prevention.

Results

Results from the survey indicated that 40% of the respondents had texted while driving. The current study did not find a difference in the frequency of texting and driving based on gender.

With respect to confidence, the survey found that 20% reported feeling very comfortable dealing with distractions (i.e. having conversations, making calls) while driving, 47.9% felt comfortable, 20.5% felt uncomfortable, and 11.6% felt very uncomfortable. Moreover, 11.2% reported that they frequently drove with distractions, 51.2% occasionally did so, 33.0% rarely did, and 4.7% never engaged in distracting tasks when driving.

Respondents were also asked about the circumstances under which they text and drive. 28.8% reported texting while in park, 15.3% at a standstill, 1.9% said in the city, 1.9% claimed they texted while in motion and on highways, 3.7% texted during all of the options provided, and 25.6% texted during none of the options. In terms of reasons they texted while driving, 26.0% only used their phones to get directions, 25.6% used them only in an emergency, 16.7% said to let people know they are on their way, 8.8% said they felt like they couldn’t wait, 2.8% to send directions. With respect to passengers, 59.1% of participants reported that they only engaged in texting and driving when they were alone, 10.7% did so with friends, 6.0% with parents, 0.9% with a child, 12.1% said they texted when driving with other people, and 11.2% did not respond.

Those from the Greater Sudbury area admitted to texting and driving more frequently than the respondents from the Manitoulin area. As for the other locations sampled (Chapleau area, LaCloche Foothills, and Sudbury East), no differences were observed. Sudbury is the least rural area sampled—the difference might reflect more time in city traffic, which includes time at a standstill. However, the majority of the respondents were from the Greater Sudbury area, and the number sampled from Manitoulin Island may be too small to reliably estimate the frequencies.

Texting and driving behaviour was reported to occur more frequently among youth in their early 20’s who have a G class license and who are in post-secondary education. Overall, the trend observed for age indicates that the youngest of the survey’s respondents (16 and 17 years) are less likely to text and drive than respondents in the older range (20–23 years). With respect to license class, respondents who had a G1 or G2 class license engaged in texting and driving behaviour less frequently than those who had a G class license. At the age of 16, in Ontario, individuals are able to obtain a G1 license. This class of license is restricting as the driver must be accompanied by a fully licensed passenger that has a minimum of four years of experience (MTO, 2013). Thus, most of these younger drivers are accompanied by an older adult (e.g. a parent), which would limit their likelihood of texting and driving.

In terms of attitudes toward texting and driving, respondents were given a series of statements with which they could agree or disagree. Almost all, 94%, said that they agreed or strongly agreed that “I personally think that texting and driving is wrong”, and 89% agreed or strongly agreed that “Texting and driving is always dangerous”. Social influence on texting and driving was shown in the results, in that 72% of respondents strongly disagreed that “People who I look up to would approve of me texting and driving” and 68% agreed or strongly agreed that “My friends would think it is inappropriate to text while driving”. However, 44% agreed or strongly agreed that “It is ok to text and drive while the vehicle is stopped”.

The survey asked which prevention strategies respondents believed would be most effective in deterring texting while driving. The most frequently suggested strategy was an increase of reminders and advertisements. A close second to this strategy was different technology to allow for safer conversations while driving. The number of respondents that suggested this strategy speaks to the heavy reliance that this age group has on their cellphones and communication. Previous research has indicated how important it is for youth to be able to be continuously connected and able to communicate (Lee, Champagne, & Francescutti, 2013). Other strategies that were selected less frequently are all related to serious consequences. For instance, the respondents reported that it would take demerit points, a crash, or a ticket to result in their behaviour changing. Furthermore, some of the respondents indicated that nothing would change their habit, insisting that out of all of the prevention strategies suggested, not even a crash or ticket would change their texting and driving behaviour. An increase in insurance rates and stricter enforcement were the two strategies that were selected least often.

When the respondents were asked if they knew the consequences of texting and driving, over half of the respondents (55%) indicated that they did not. This result suggests that this age group may need more information about the legal consequences of texting and driving.

One limitation of the survey phase was the small sample size from locations other than those in the Greater Sudbury area. Although the current study did not identify any differences in texting and driving behaviour based on location other than between Sudbury and Manitoulin, it is possible that there was a difference between rural and urban youth and their texting and driving behaviour, but due to a small sample size of the rural communities, the survey was unable to systematically explore this question.

Summary of youth survey findings

Texting while driving is prevalent among young drivers in Northeastern Ontario, with 40% of survey respondents reporting that they engaged in this behaviour. The majority, however, agree that texting and driving is wrong, demonstrating a difference between attitudes in general and their own personal behaviour. Many reported that they feel comfortable driving with distractions, perhaps because they are overestimating their own skills and underestimating their risks.

The findings suggest that those in their early twenties should be targeted as most at risk for texting and driving. This age group are able to drive alone with their G license and feel confident enough to perform this task (Weilenmann & Larsson, 2002), but they are still some of the least experienced and youngest drivers on the road, and the most likely to take risks while driving (Beck, Hartos, & Simons-Morton, 2002; Mayhew, Simpson & Pak, 2003; Olsen, Lee, Simons-Morton, 2007;). As for prevention, youth indicate wanting reminders, better technology or a physical or legal consequence to prevent them from texting and driving. Over half of the respondents stated that they do not know the legal consequences to texting and driving behaviour, suggesting that awareness and education should be part of a prevention strategy.

Advertisement attention as measured by eye-movement

Public health advertisements may be a strategy for changing texting and driving behaviour. This phase was deemed important given current anti-texting and driving campaigns run by the Public Health Sudbury & Districts. These campaign materials were measured in this study. However, in order to achieve the goal of preventing a target behaviour, advertisements must captivate attention of the viewer long enough for the message to be perceived and processed (Mackenzie, 1986). Therefore, when creating public health advertisements, it is important to explore what components of the advertisement attract the most attention in order to for the advertisement to be as effective as possible. There are various components of advertisements that may influence how much attention an advertisement holds. The audience’s attention may be influenced by images, by text-based messages, or by the amount of image or text being displayed (Pieters & Wedel, 2004). Furthermore, the components that may attract attention might differ depending on the message that is being conveyed.

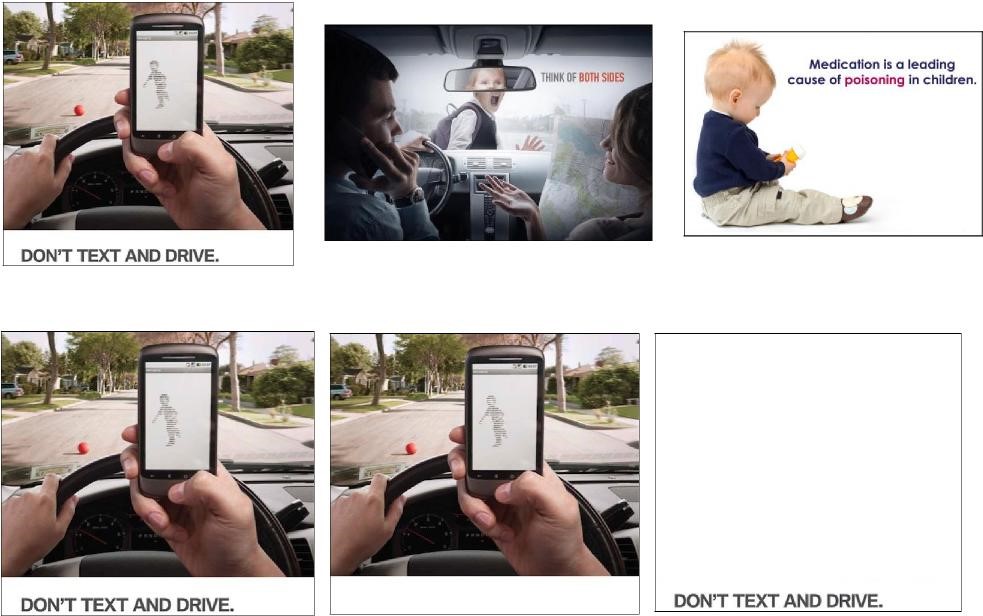

The study examined eye-movement patterns of youth while viewing texting and driving prevention advertisements to determine which format attracts the most attention. Participants viewed non-driving, general distracted driving and anti-texting and driving advertisements, with either text only, image only, or text plus image contents.

The goal of the current study was to further understand which content type of public health advertisements (text-based, image-based, or a combination of both) is most successful at captivating youths’ attention for texting and driving advertisements. This question has never been previously explored for this type of advertisement. The sample was youth between the ages of 16 to 24 years old, the most susceptible age group for texting and driving.2

Method

Thirty participants from the City of Greater Sudbury were recruited for the current study. The sample consisted of 23 females and 9 males between the ages of 16 and 24 years. All the participants reported normal or corrected to normal vision and had a valid driver’s license. Participants were recruited through acquaintances, public advertisements throughout Laurentian University and a volunteer pool of student participants through the Cognitive Health Research Laboratory.

Participants viewed three different types of public health advertisements. The advertisement conditions consisted of texting and driving, general distracted driving, or general public health advertisements that are unrelated to driving. Five advertisements were used for each of the conditions, consisting of 15 original advertisements (sample in upper panel of Figure 1). All of the advertisements consisted of no more than one sentence each in word length. All 15 original advertisements were then altered to create an image only condition and text only condition, creating a final sample of 45 public advertisements used throughout the study (sample in lower panel of Figure 1). Participants viewed all of the advertisement conditions (original/unaltered, text-only, and image-only) in a randomized order.

Eye tracking

Participants’ eye movements were tracked with the SR Research Eye Link 1000 system. The system consists of an infrared camera that tracks participants’ corneal reflection. The eye-tracking equipment also consisted of a head and chin rest used to stabilize head movements.

Survey

After the eye-tracking portion, all participants completed an online survey, using the same questionnaire used in the survey phase, evaluating whether the participants had texted and driven before, and if so, where, why, and under what conditions.

Data analysis

Eye movement measures were coded using the Eyelink Data viewer software. This program presents the advertisements and superimposes the position of all fixations onto them. Eye-tracking variables of interest were mean dwelling time on each of the whole advertisements as well as dwell time on specific zones on the advertisements (image zone and text zone).

Results

The study examined youth’ exploration of anti-texting and driving advertisements with eye-tracking measures in order to determine which content was most successful at maintaining attention. The differences in attention to text and image content varied as a function of the content of the advertisement itself. For general advertisements (unrelated to distracted driving), results revealed that the advertisements containing image and text content together resulted in more time spent on the advertisement, followed by image only content and then text only content. For distracted driving, and for anti-texting and driving advertisements in particular, participants spent more time on text only content than image only content, and more on image only that the image and text.

In examining dwell time on text versus image on the unaltered advertisements, participants spent the majority of their time on images rather than text. These results, combined with the observation that for anti-texting and driving advertisements participants spent more time when they contained text only, suggest that including images might actually encourage the participants to withdraw their attention from the text.

In examining the differences between texters and non-texters as self-reported in the survey, results indicated that there are no differences between the way texters and non-texters view the advertisements.

The advertisements used were not controlled based on their content. For example, text size and font type varied in the text-based advertisements, and image size and content, such as reality-based or cartoon, were not controlled.

Summary of eye tracking findings

The purpose of this study was to examine which content type in public health advertisements was most successful at attracting youth’ attention for anti-texting and driving advertisements. The results indicated that text-based content on the anti-texting and driving advertisements was most effective at attracting attention.

The first step to creating effective advertisements is to attract the target audience’s attention. As youth are the most susceptible to texting and driving related accidents it is especially important for the public health advertisements on this topic to be created to grasp their attention. Based on the current results, future public health advertisements on anti-texting and driving might attract greatest attention if they contain only text-based messages.

Interviews

The main objectives of the interviews were to hear from young drivers about their perceptions of texting and driving, their reasons for texting and driving and their knowledge of the consequences. The participants were also asked about their ideas for effective strategies to reduce texting and driving among young drivers. The ability to capture ideas for effective strategies to reduce texting and driving among young drivers directly from the target population was a key piece of this study, as rates of texting and driving among this age group remain dangerously high and effective prevention strategies are needed.

With the results from the interviews, the objective was to triangulate data gained from the literature review, surveys, eye tracking studies and interviews to provide an in-depth view of texting and driving among young drivers in Northeastern Ontario. This information will be used to implement innovative and effective anti-texting and driving strategies targeted to young drivers within the Public Health Sudbury & Districts catchment area, that are informed by the target population.

Method

15 semi-structured interviews were conducted for this phase of the study. Seven males and eight females participated, and all were between 16-24 years of age.. All participants were currently living within the service-delivery area of Public Health Sudbury & Districts (including Chapleau, Sudbury East, Manitoulin Island, Espanola, and the City of Greater Sudbury), had a valid driver’s license, and admitted to texting and driving. The interview questions included questions about their ideas for effective prevention strategies, therefore participants needed to be unbiased and not previously exposed to existing strategies.

Each interview was voice-recorded and transcribed. Each of the transcripts were separately coded by three individual researchers for data quality purposes. Coded transcripts were then compared and contrasted by a minimum of two researchers to create the themes and final coding structure.

Results

An important theme explored through the interviews was the perceptions and behaviours related to the risk of texting and driving, including risk-perception, perception of ability, disregard of the risks, understanding of the risks, and recognition of risk and change in behaviour. Participants understood the consequences of texting and driving, but still engaged in the behaviour. They considered it a matter of personal choice, and cited lack of willpower as a reason for not changing their behaviour even while knowing that it posed a risk. One participant stated “Ultimately I think it would just, it will be willpower for me to just put it down”. Another participant stated “I tend to text and drive a lot despite the fact that I think it’s dangerous. It’s something I shouldn’t be doing and I know it but I do it anyways.” As shown in the survey results, interview participants were also more likely to text and drive when they were alone.

Consequences of texting and driving explored through the interviews were those of parents, legal, financial (including the penalties for texting and driving at the time of the interview), and societal. The majority of the participants were unaware of the legal and financial penalties. If found texting and driving, drivers can be fined between $300-$1,000 and lose 3 demerit points (CBC News, 2015). Drivers can also expect insurance rates to increase when convicted. Despite the consequences, participants stated that tickets and increasing insurance would not be sufficient to prevent them from texting and driving.

Personal consequences and experiences were the most prominent deterrent discussed by the youth. One participant stated that “If I ever one day get into an accident because of that, I mean I’d be kicking myself because that’s the dumbest thing that I could of done.” While another stated that “Nothing serious has happened to me to prevent me from completely stopping.”

Potential prevention strategies participants suggested included safer technology such as hands-free applications and bluetooth, providing awareness and education through advertising and social media, and targeting younger children through school awareness campaigns.

Summary of interview findings

A key contribution of this study is that it featured youth who admitted to texting and driving, the population that public health wants to target. The interviews provided a platform to explore the perceptions of texting and driving among young drivers in greater depth, which provided many useful results to implement in prevention strategies conducted by Public Health Sudbury & Districts in the future.

Key findings from the interviews included young drivers describing their texting and driving behavior as something they do despite being aware of the risks. The participants described texting and driving a matter of personal choice, and admitted that the legal and financial consequences would not be sufficient to prevent them from texting and driving. Perceptions of successful prevention strategies included hands-free communication, targeting younger children through school awareness campaigns, and education and awareness raising campaigns through social media.

Overall study conclusion

In conclusion, this study has provided a breadth of knowledge relating to texting and driving among youth. Youth have the highest prevalence of texting and driving compared to other age groups, although most youth perceive that this behaviour is dangerous. In 21% of fatal collisions involving Ontario youth, texting and driving was the main factor. Due to the increasing prevalence of texting and driving among youth, there is cause for concern for public health in Northeastern Ontario and a need for prevention strategies. This study conducted by Public Health Sudbury & Districts and Laurentian University utilized a literature review, a survey of youth in Northeastern Ontario, an eye-tracking study, and interviews with Northeastern Ontario youth to gain insight for future public health prevention strategies. This study has identified several strategies and implications for the prevention of texting and driving among Northeastern Ontario youth.

Implications for prevention strategies in Northeastern Ontario

- Many young drivers persist in continuing a behaviour that they know is dangerous. Youth report that it would take a crash or a ticket to stop them from texting and driving, and some report that nothing would stop them. Thus, education that advises on the dangers of texting and driving, or that aims to increase fear, is not likely to change the behaviour.

- 40% of youth surveyed admit to texting and driving.

- Those who perceive the risk to be lower are more likely to text and drive.

- Those who perceive high peer approval for texting and driving perceive the risk to be lower.

- Youth reported not being fully aware of the fact that it is against the law to text and drive and that there are penalties for doing so. Few survey and interview participants could actually state the correct legal and financial penalties. Education could increase knowledge, but it appears that knowledge alone will not be sufficient to change behaviour.

- Texting and driving behaviour seems resistant to change, partly because texting is a social norm and is of high value as a tool for instant connection. Because social norms appear to be contributing to texting and driving, prevention strategies should be targeted to changing the norms among young people. Messages delivered by peers and socially important personalities, or with reference to the perceptions of peers, could be explored as channels for prevention education.

- Education that provides strategies to make texting and driving less appealing (such as personalizing the risks to self and others) or less accessible (such as putting the phone out of reach) may be promising. Education that increases fear without providing suggestions about what else to substitute for the risky behaviour is often discounted and, therefore, ineffective. Alternative, explicit strategies tailored to the specific situations or reasons for texting and driving could be provided through education, to address such situations as:

- Common reasons for texting and driving include emergency situations, to get directions and to tell people their whereabouts. What other strategies could be used instead?

- Youth text and drive most often when they are at a stand-still and when alone. What other behaviours could be substituted? Another area to address is that youth are more likely to text and drive when they are alone than if they have a passenger. Perhaps targeted messaging about if you wouldn’t do it in front of others it is not alright to do it when you are alone.

- Youth in their twenties text more than younger youth, which may be because younger youth are beginner drivers and, due to license requirements, often drive with their parents. Thus, youth drivers driving alone or with peers may be a particular target audience for texting and driving prevention.

- Technology may provide some safer ways to use cellphones while driving, but even these approaches carry greater risk than driving without distractions. Promoting technology such as hands-free applications must be done with awareness that the use of technology may incorrectly reduce the perception of risk.

- Given evidence of the illusion of invincibility (Adeola & Gibbons, 2013) among young drivers, ways to heighten their perception of risk to be more accurate should be considered, along with concrete strategies to reduce the anxiety associated with risk. Simulations that demonstrate the actual effects of distracted driving on an individual’s behaviour may provide tangible evidence of the risk, but simulation would not be available as a widespread strategy.

- Advertisements were suggested as a possible strategy for education. This research shows that text-based ads about texting and driving maintain longer attention.

Appendix

Figure 1.

Advertisement Types: Texting and Driving, Distracted Driving and General (Upper panel); Content Types: such as unaltered condition, image only condition and text only condition (Lower panel).

- Dénommée, J., Foglia, V., Roy-Charland, A., Turcotte, K., Lemieux, S., & Yantzi, N. (accepted). Cell phone use and young drivers. Canadian Psychology.

- Foglia, V., A., Roy-Charland, D. Leroux, S. Lemieux, N. N. Yantzi, T. Skjonsby-McKinnon, S. Fiset, et D. Guitard. (accepted). When pictures take away from the message: An examination of young adults’ attention to anti-texting and driving advertisements. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology/Revue Canadienne de psychologie expérimentale.

References

Adeola, R. & Gibbons, M. (2013). Get the Message. Journal of Trauma Nursing, 20(3), 146-149. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/jtn.0b013e3182a172cc

Amado, S., & Ulupinar, P. (2005). The effects of conversation on attention and peripheral detection: Is talking with a passenger and talking on the cell phone different? Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 8(6), 383-395.

Beck, K.H., Hartos, J., Simons-Morton, B. (2002). Teen driving risk: The promise of Parental influence and public policy. Health Education Behaviour, 29:73e84.

Buckley, L., Chapman, R., & Sheehan, M. (2014). Young Driver Distraction: State of the Evidence and Directions for Behavior Change Programs. Journal Of Adolescent Health, 54(5), S16-S21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.021

Canadian Association of Mental Health (CAMH), (2013). Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey. Extracted on November 10, 2016: http://www.camh.ca/en/research/news and publications/ontario-student-drug-use-and-health-survey/Documents/ 2013%20OSDU.

CBC News. (2015, June 2). Distracted driving penalties increase under new Ontario law.

Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/distracted-driving-penalties-increase-under-new-ontario-law-1.3096785

Cismaru, M. (2014). Using the Extended Parallel Process Model to Understand Texting While Driving and Guide Communication Campaigns Against It. Social Marketing Quarterly, 20(1), 66-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1524500413517893

Foss, R. D., & Goodwin, A. H. (2014). Distracted driver behaviors and distracting conditions among adolescent drivers: Findings from a naturalistic driving study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(5), S50-S60.

Garner, A., Fine, P., Franklin, C., Sattin, R., & Stavrinos, D. (2011). Distracted driving among adolescents: challenges and opportunities. Injury Prevention, 17(4), 285-285. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2011-040096

Gaspar, J. G., Street, W. N., Windsor, M. B., Carbonari, R., Kaczmarski, H., Kramer, A. F., & Mathewson, K. E. (2014). Providing views of the driving scene to drivers’ conversation partners mitigates cell-phone-related distraction. Psychological science, 25(12), 2136-2146.

Hafetz, J., Jacobson, L., García-España, J., Curry, A., & Winston, F. (2010). Adolescent drivers’ perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages of abstention from in-vehicle cell phone use. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 42(6), 1570-1576. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2010.03.015

Harrison, M. (2011). College students’ prevalence and perceptions of text messaging while driving. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 43(4), 1516-1520. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2011.03.003

He, J., Chaparro, A., Nguyen, B., Burge, R. J., Crandall, J., Chaparro, B., … & Cao, S. (2014). Texting while driving: Is speech-based text entry less risky than handheld text entry?. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 72, 287-295.

Hosking, S. G., Young, K. L., & Regan, M. A. (2009). The effects of text messaging on young drivers. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 51(4), 582-592.

Huang, D., Kapur, A., Ling, P., Purssell, R., Henneberry, R., & Champagne, C. et al. (2010). CAEP position statement on cellphone use while driving. CJEM, 12(04), 365-370. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s1481803500012483

Jacobson, P. & Gostin, L. (2010). Reducing Distracted Driving. JAMA, 303(14), 1419. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.414

Klauer, S. G., Guo, F., Simons-Morton, B. G., Ouimet, M. C., Lee, S. E., & Dingus, T. A. (2014). Distracted driving and risk of road crashes among novice and experienced drivers. New England Journal of Medicine, 370(1), 54-59.

Lee, V. K., Champagne, C. R., & Francescutti, L. H. (2013). Fatal distraction Cell phone use while driving. Canadian Family Physician, 59(7), 723–725.

Lee, V. K., Champagne, C. R., & Francescutti, L. H. (2013). Fatal distraction Cell phone use while driving. Canadian Family Physician, 59(7), 723–725. doi:10.1016/S0001-4575(02)00083-0

Llerena, L. E., Aronow, K. V., Macleod, J., Bard, M., Salzman, S., Greene, W., Haider, A., & Schupper, A. (2015). An evidence-based review: distracted driver. Journal of trauma and acute care surgery, 78(1), 147–152. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000487

MacKenzie, S. B. (1986). The role of attention in mediating the effect of advertising on attribute importance. Journal of Consumer Research, 174–195.

Mayhew, D.R., Simpson, H.M., Pak, A. (2003) Changes in collision rates among novice drivers during the first months of driving. Accident Analysis and Prevention,35:683e91.

Ministry of Transportation. (2013, September 13th). Graduated licensing requirements: Level one (Class G1). Retrieved from https://www.ontario.ca/document/official-mto-drivers-handbook/getting-your-drivers-licence#level-one

Nabutilan, Aghazadeh, Nimbarte, Harvey & Chowdhury, 2011 Adeola, R. & Gibbons, M. (2013). Get the Message. Journal Of Trauma Nursing, 20(3), 146-149. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/jtn.0b013e3182a172cc

Nelson, E., Atchley, P., & Little, T. D. (2009). The effects of perception of risk and importance of answering and initiating a cellular phone call while driving. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 41(3), 438–444. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2009.01.006

Neyens, D. & Boyle, L. (2007). The effect of distractions on the crash types of teenage drivers. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 39(1), 206-212. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2006.07.004

Neyens, D. & Boyle, L. (2008). The influence of driver distraction on the severity of injuries sustained by teenage drivers and their passengers. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 40(1), 254-259. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2007.06.005

Olsen, E.C., Lee, S.E., Simons-Morton, B.G. (2007). Eye movement patterns for novice teen drivers does 6 months of driving experience make a difference? Transportation Research Record, 8e14.

Olsen, E.O.M., Shults, R.A., Eaton, D.K., (2013). Texting while driving and other risky motor vehicle behaviors among US high school students. Pediatrics 131 (6), e1708–e1715.

Pieters, R., & Wedel, M. (2004). Attention capture and transfer in advertising: Brand, pictorial, and text-size effects. Journal of Marketing, 68(2), 36–50.

Rhodes, N., Pivik, K., (2011). Age and gender differences in risky driving: the roles of positive affect and risk perception. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 43(3),923–93.

Rumschlag, G., Palumbo, T., Martin, A., Head, D., George, R., & Commissaris, R. L. (2015). The effects of texting on driving performance in a driving simulator: The influence of driver age. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 74, 145-149.

Schlehofer, M., Thompson, S., Ting, S., Ostermann, S., Nierman, A., & Skenderian, J. (2010). Psychological predictors of college students’ cell phone use while driving. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 42(4), 1107-1112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2009.12.024

Simons-Morton, B. G., Ouimet, M. C., Zhang, Z., Klauer, S. E., Lee, S. E., Wang, J., Chen, R., Albert, P., & Dingus, T. A. (2011). The effect of passengers and risk-taking friends on risky driving and crashes/near crashes among novice teenagers. Journal of Adolescent Health, 49(6), 587-593.

Strayer, D. L., Drews, F. A., & Johnston, W. A. (2003). Cell phone-induced failures of visual attention during simulated driving. Journal of experimental psychology: Applied, 9(1), 23–52. doi: 10.1037/1076-898X.9.1.23

Struckman-Johnson, C., Gaster, S., Struckman-Johnson, D., Johnson, M., & May-Shinagle, G. (2015). Gender differences in psychosocial predictors of texting while driving. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 74, 218-228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2014.10.001

Thumser, Z. C., & Stahl, J. S. (2013). Handheld cellular phones restrict head movements and range of visual regard. Human Movement Science, 32(1), 1–8. doi: 0.1016/j.humov.2012.03.002

Tractinsky, N., Ram, E. S., & Shinar, D. (2013). To call or not to call—That is the question (while driving). Accident Analysis & Prevention, 56, 59-70.

Tucker, S., Pek, S., Morrish, J., & Ruf, M. (2015). Prevalence of texting while driving and other risky driving behaviors among young people in Ontario, Canada: Evidence from 2012 and 2014. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 84, 144-152. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2015.07.011

Weilenmann, A., & Larsson, C. (2002). Local use and sharing of mobile phones. In B. Brown, N. Green & R. Harper (Eds.) Wireless World: Social and Interactional Aspects of the Mobile Age. Springer Verlag, pp. 99-115.

Wilson, F. & Stimpson, J. (2010). Trends in Fatalities From Distracted Driving in the United States, 1999 to 2008. American Journal Of Public Health, 100(11), 2213-2219. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2009.187179

Young, K. & Lenné, M. (2010). Driver engagement in distracting activities and the strategies used to minimise risk. Safety Science, 48(3), 326-332. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2009.10.008.

This item was last modified on February 3, 2025