Drink spiking

Drink spiking is the act of secretly adding a substance to someone’s drink without their knowledge or consent. Substances used to spike a drink may be colourless, odourless, and tasteless and are added to a drink with the intention of causing harm or taking advantage of the person who has consumed the spiked drink.

The effects of a spiked drink can vary depending on the substance that has been added, but they may include feeling drunk or unwell despite having limited or no alcohol, nausea and vomiting, and loss of control or consciousness. In severe cases, drink spiking can lead to serious injury or even death. It also makes one more vulnerable to sexual assault, human trafficking, robbery, abduction, and injury.

It is important to be aware of the risks of drink spiking and to take steps to protect yourself and others. This includes never leaving your drink unattended, not accepting drinks from strangers, and only drinking from sealed containers. If you suspect that your drink has been spiked or if you feel unwell after drinking, it is important to seek medical attention immediately and not leave the venue alone.

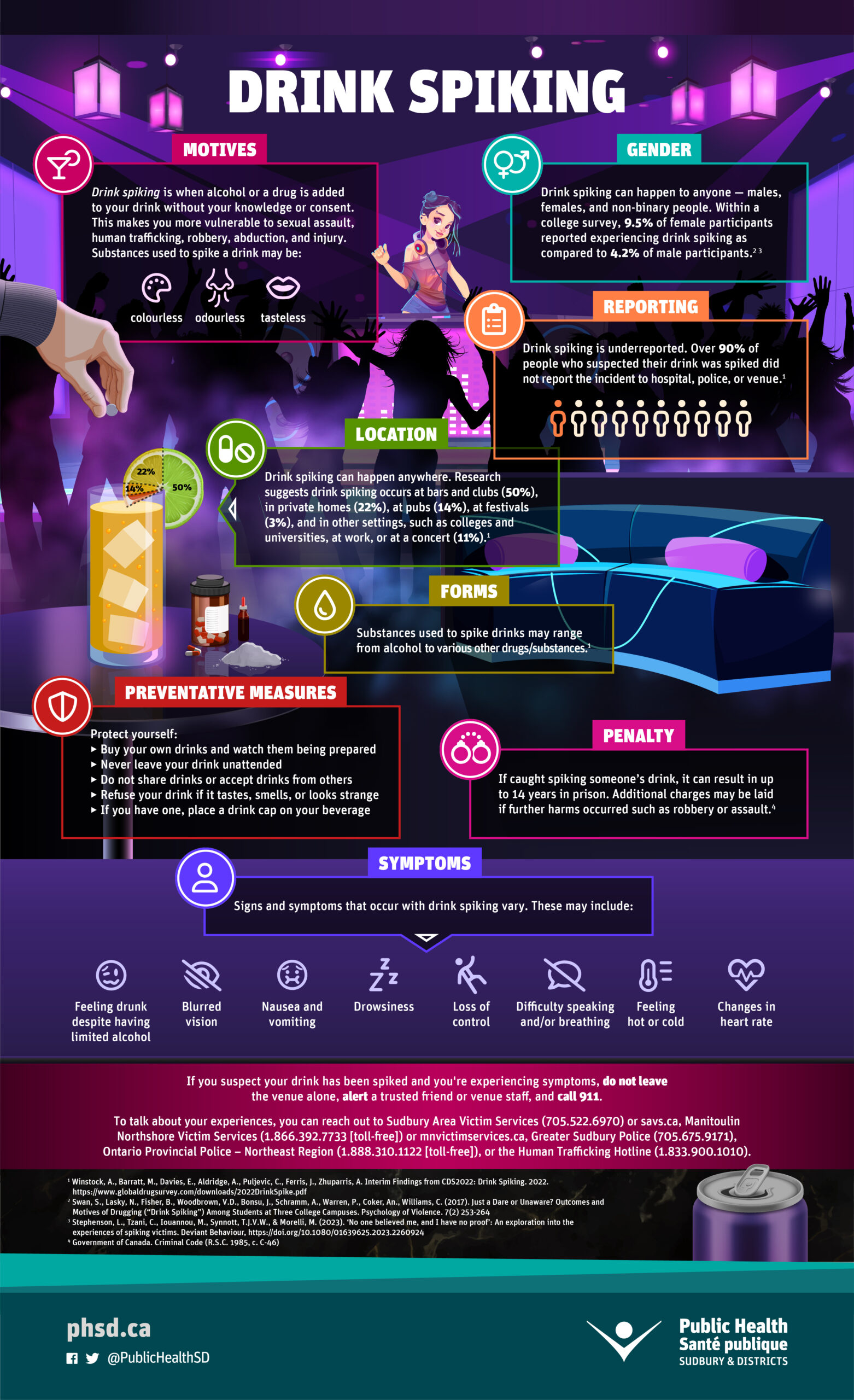

To learn about possible signs and symptoms, strategies to protect yourself and others, and other important information about drink spiking, see the infographic below.

The information displayed in the infographic above is displayed in an accessible format below.

Drink spiking

Motives

Drink spiking is when alcohol or a drug is added to your drink without your knowledge or consent. This makes you more vulnerable to sexual assault, human trafficking, robbery, abduction, and injury. Substances used to spike a drink may be: colourless, odourless, tasteless.1

Gender

Drink spiking can happen to anyone — males, females, and non-binary people. Within a college survey, 9.5% of female participants reported experiencing drink spiking as compared to 4.2% of male participants.2,3

Reporting

Drink spiking is underreported. Over 90% of people who suspected their drink was spiked did not report the incident to the hospital, police, or venue.1

Location

Drink spiking can happen anywhere. Research suggests drink spiking occurs at bars and clubs (50%), in private homes (22%), at pubs (14%), at festivals (3%), and in other settings, such as colleges and universities, at work, or at a concert (11%).1

Forms

Substances used to spike drinks may range from alcohol to various other drugs/substances.1

Preventive measures

Protect yourself:

- Buy your own drinks and watch them being prepared

- Never leave your drink unattended

- Do not share drinks or accept drinks from others

- Refuse your drink if it tastes, smells, or looks strange

- If you have one, place a drink cap on your beverage

Penalty

If caught spiking someone’s drink, it can result in up to 14 years in prison. Additional charges may be laid if further harms occurred such as robbery or assault.4

Symptoms

- Feeling drunk despite having limited alcohol

- Blurred vision

- Nausea and vomiting

- Drowsiness

- Loss of control

- Difficulty speaking and/or breathing

- Feeling hot or cold

- Changes in heart rate

If you suspect your drink has been spiked and you’re experiencing symptoms, do not leave the venue alone, alert a trusted friend or venue staff, and call 911.

To talk about your experiences, you can reach out to Sudbury Area Victim Services (705.522.6970) or savs.ca, Manitoulin Northshore Victim Services (1.866.392.7733 [toll-free]) or mnvictimservices.ca, Greater Sudbury Police (705.675.9171), Ontario Provincial Police – Northeast Region (1.888.310.1122 [toll-free]), or the Human Trafficking Hotline (1.833.900.1010).

- Winstock, A., Barratt, M., Davies, E., Aldridge, A., Puljevic, C., Ferris, J., & Zhuparris, A. (2022). Interim findings from CDS2022: Drink spiking. Global Drug Survey. https://www.globaldrugsurvey.com/downloads/2022DrinkSpike.pdf

- Swan, S., Lasky, N., Fisher, B., Woodbrown, V. D., Bonsu, J., Schramm, A., Warren, P., Coker, A. N., & Williams, C. (2017). Just a dare or unaware? Outcomes and motives of drugging (“drink spiking”) among students at three college campuses. Psychology of Violence, 7(2), 253–264. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000060

- Stephenson, L., Tzani, C., Iouannou, M., Synnott, T. J. V. W., & Morelli, M. (2023). ‘No one believed me, and I have no proof’: An exploration into the experiences of spiking victims. Deviant Behavior. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2023.2260924

- Government of Canada. (1985). Criminal Code (RSC 1985, c C-46). https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-46/

e (1.833.900.1010).

1 Winstock, A., Barratt, M., Davies, E., Aldridge, A., Puljevic, C., Ferris, J., Zhuparris, A. Interim Findings from CDS2022: Drink Spiking. 2022.

https://www.globaldrugsurvey.com/downloads/2022DrinkSpike.pdf

2 Swan, S., Lasky, N., Fisher, B., Woodbrown, V.D., Bonsu, J., Schramm, A., Warren, P., Coker, An., Williams, C. (2017). Just a Dare or Unaware? Outcomes and Motives of Drugging (“Drink Spiking”) Among Students at Three College Campuses. Psychology of Violence. 7(2) 253-264

3 Government of Canada. Criminal Code (R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46)

This item was last modified on May 12, 2025